Why are some archival materials restricted?

Feature of the heavily censored Mirkevet ha-Mishneh, 1551, Courtesy of the Special Collections.

As Reference Archivist at the JPL, my main responsibility is to aid researchers in accessing our records. Though it might sound counterintuitive, a considerable part of this mandate includes identifying what can be accessed. While a large majority of our archive’s records are freely available for research, there are instances where materials – or, in rare cases, entire fonds – have what we call “restricted access”.

Two fields of RAD, the Rules for Archival Description, allow archivists to detail any restrictions placed on materials within a given collection.

There are two types of restrictions: privacy and copyright.

Privacy restrictions are placed by the record’s donor. There are any number of reasons why a donor might want to keep their donated materials private. Perhaps they contain sensitive family histories, like a parent’s personal diaries or correspondences; perhaps they contain confidential information related to an institution’s internal functions. Many people donate to an archive to ensure the long-term preservation of materials that they deem significant. The access to these materials might be a lower priority than the guarantee that they stay safe and cared for.

When a fonds has privacy restrictions, there are usually terms that determine exceptions. The two most common terms are:

an expiration date on the restriction (ex., 20 years after the time of donation), or

the option for a user to request access from the donor

As an archive, one of our main mandates is towards public education. As such, we rarely accept material that is under indefinite restriction.

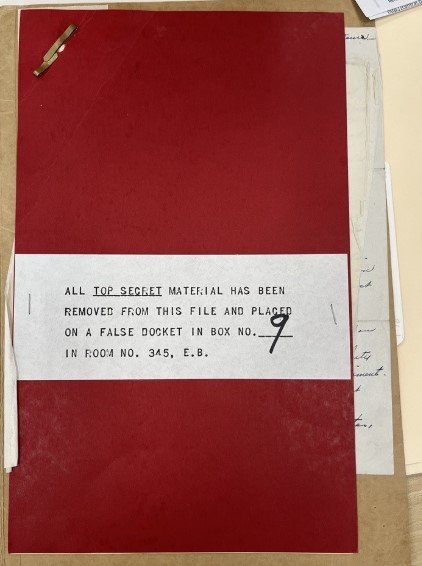

A TOP SECRET file from our Outreach team’s recent visit to Library and Archives Canada.

The second form that you might encounter is that of copyright restrictions. Copyright typically comes into effect with published works. Published material by nature are not usually considered archival, given that they are not unique records. That being said, many of the collections that we host contain at least a handful of published materials, often in the form of newspaper clippings or other periodicals. These secondary sources often serve to complement the primary sources that we’d find in the rest of the collection, providing context on the hyper-specific letters and ephemera that might comprise a typical fonds. However, these published materials are also more likely to fall under copyright.

Unlike privacy restrictions, copyright restrictions are usually specific to reproduction. This distinction means that a researcher is allowed to come in to consult the copyrighted material, but we do not have the power to share it for publication. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule. Some copyrighted material might not even be available for consultation – at least, not until it becomes fair use, which in Canadian law is 70 years following the creator’s death.

Even us archivists are still trying to demystify copyright law and the search for the oft-elusive “rights holder.” However, if you ever need help understanding a restriction of any kind, you are always welcome to reach out to the Reference Archivist (that’s me!), and we’ll walk you through what we can.