On translation with context, Part I

Longstanding JPL community member Anna Fishman Gonshor recently sat down with us to talk about why her volunteer work in the Archives feels so important to her. Highlights from her August 4, 2025 interview have been divided into this and next month's blog posts, edited for length and clarity.

***

On Yiddishland around the world

I think one of the really exciting aspects of these archives is that the Yiddish literary world was connected on many continents. It wasn’t just the writers of Montreal who associated with the Montreal writers. It was that the writers of Montreal were read in Poland, in Ukraine, in France, in South America, in Israel/Palestine, and the other way around, too. For instance, I’ll never forget one of the encounters I had in the archives with a letter that mentions Hertz Kalles, who was then director of the [Jewish Public] Library, from someone in Warsaw. And then I opened the Warsaw Yiddish papers [literarishe bleter] and there is the annual report of the Jewish Public Library of 1932 sent in by Hertz Kalles and Rochl Eisenberg. So clearly Yiddish culture was not isolated, and Yiddishland wasn’t just in Poland. Yiddishland was in fact around the world.

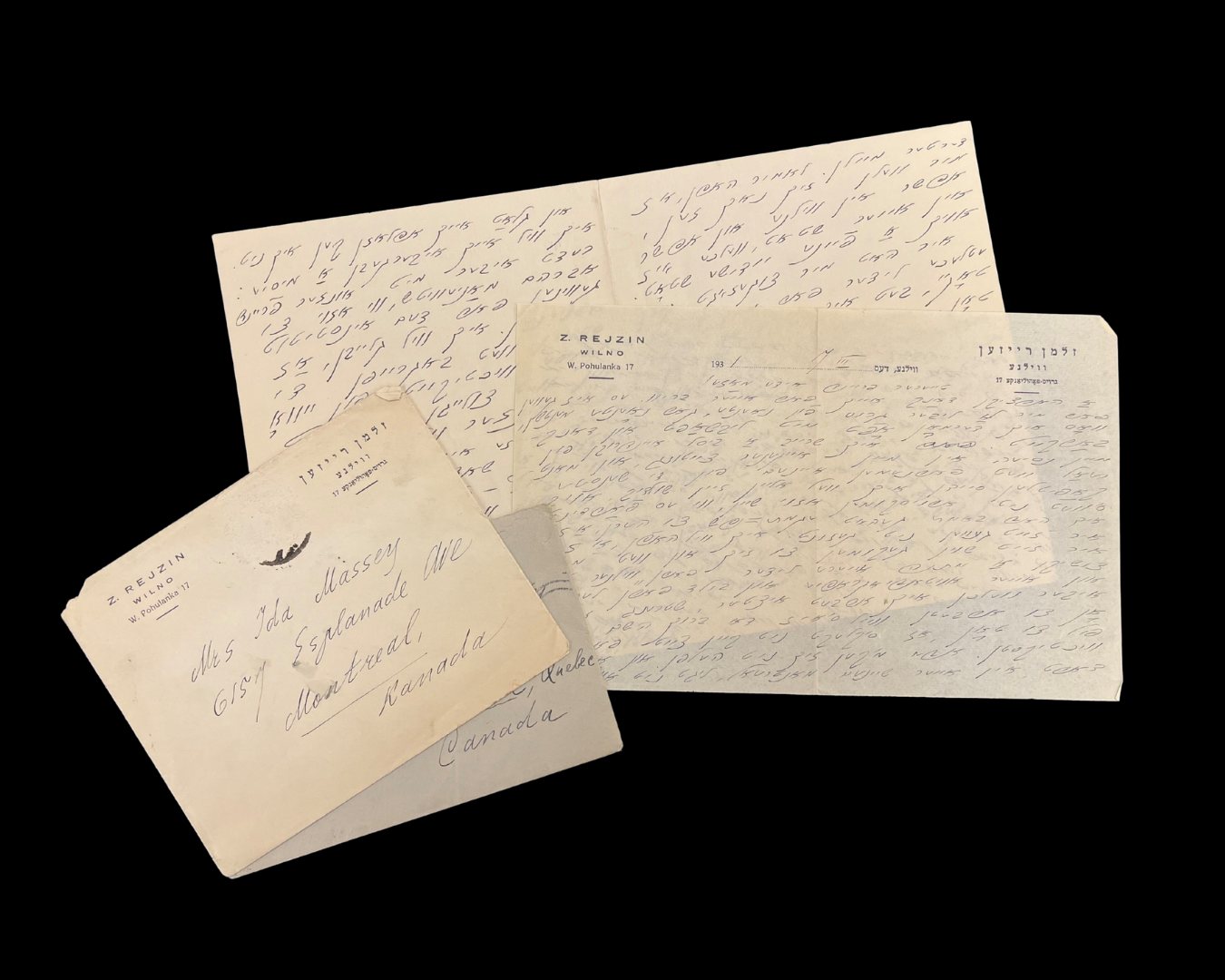

Zalman Reisen letters sent from Warsaw, Poland to Ida Maze in Montreal, 1931. They mention Hertz Kalles, president of the Jewish Public Library at the time of writing. Courtesy of the JPL Archives, Ida Maze Fonds, 1090-[18]-009/015-001.

***

On letters, memoirs, diaries and context

What’s fascinating about letters in general as opposed to, let’s say memoirs, is the immediacy of them. They are written at a specific time on a specific day, depending on the weather, and how people are feeling at that given moment and how they are affected by what’s going on around them, whether it’s personal, municipal or whatever is going on in the world. And that’s reflected in the letters. What they’re writing on the published page is not what you see in a letter, and the responses to those letters, whether something is misinterpreted, or read differently, and the back and forth is really wonderful in terms of understanding who these writers were and particularly the Yiddish writers and their difficulty in publishing, the general poverty that many of them lived in. And there’s the issue of the particular problems women writers had, and what they were up against. They share this with each other, and encourage each other. It’s just an incredible opportunity to see them as human beings and not just as writers.

I’m trained as a historian, but I also taught literature because I’m committed to understanding the author’s life, the times that they lived in, what they encountered, how they saw the world and how you see that in their work. It’s not just about literary theory. [In letters,] they’re just themselves. Memoires are dangerous. Not only because there’s clearly a choice of how to remember. The letter is the immediacy of the moment. You get that from diaries too, but not quite the same way, because there’s a consciousness in a diary that someone may read it at a different time. With letters, there’s no inhibition. They’re meant to be read by someone specific in a specific moment, but it’s not to the world.

And it's not just a question of translating; it’s never a question just of translating. Aside from the fact that each language has its idioms and there are so many different words for the same thing; why did, in this letter she say this this way and then in another letter she said it with a different word, you know? Translating is glossing unless you bring a context to it.

***

Anna Fishman Gonshor has been a part of the JPL’s community for more than 70 years. She grew up attending our children’s library, and in the 1980s became Executive Director, then President. Most recently, she has been a consistent volunteer in our archives, working on translating the item level descriptions of many of our archival fonds from Yiddish to English.