de bello judaico [spanish]

(Seville : Juan Cromberger, 1536)

-

Around 75 CE, Josephus wrote De Bello Judaico (“The Jewish War”), one of 5 primary sources available on the first Jewish-Roman War (55-73 CE). The first 2 of its 7 volumes summarize Jewish history from Antiochus IV Ephiphanies’ capture of Jerusalem to the War’s first stages. Subsequent volumes detail the War’s events and conclude with the death of the last Sicarii (Jewish Zealots), whose stealthy yet very public attacks with small daggers on Romans and Roman sympathizers boldly proclaimed their fierce opposition to Rome’s occupation of Judea.

Josephus opens De Bello with a derogatory salutation to his native Jewish community as “upper barbarians”. He then seems to try countering his evident bias by claiming he merely wants to refute anti-Roman narratives about the War, and even assigns Judea’s corrupt and incompetent Roman governors some responsibility for the conflict. However, he ultimately blames it on Zealots instigating the masses against him and other aristocratic leaders. He opines that Jews should peacefully accept Roman rule because it was God-given. Unlike the Josephus who composed Antiquities of the Jews 20 years later, the Josephus of De Bello makes no attempt to reconcile Jewish and Roman world-views.

Although the earliest extant manuscript, in Greek, of Josephus’s work forms the basis of all early translations, scholars generally agree that the original manuscript was in Aramaic, although none survives. Therefore, though Josephus supposedly supervised the Greek version, the Grecian translator’s interpretation colored that version. Several subsequent translations based on the Greek indicate a more liberal interpretation than do others. For example, the Slavonic version — apparently completed in Rus nearly a millennia after the author’s death — contains what is described as a “very free translation”, with a considerable amount of text found nowhere in any Greek version. An early Hebrew version also exists, with a similar number of textual disparities versus the Greek version. Both the Slavonic and Hebrew exemplify a lengthy history of translation, interpolation, and modification of Josephus’s original text.

-

Jerusalem-born Titus Flavius Josephus, né Yosef ben Matityahu (37 CE -100 CE) left behind a body of historical writings that, even today, make him a controversial figure. While they include a unique, valuable contemporaneous record of both the 1st-century Jewish rebellions against Roman rule in the Holy Land region known as Judea – as well as of Jesus of Nazareth – they also contain many autobiographical details that still remain as disputed and suspect as Josephus’s true loyalties. Regardless of one’s verdict about that, his works give readers a sense of the competing influences that his native Judaism and emerging Christianity had upon him.

Josephus and his brother had parents who represented the era’s transition between Jewish and non-Jewish control in Judea. His mother descended from the Hasmonean royal dynasty, the territory’s last Jewish rulers; his father, a high-ranking Kohen (Jewish priest), became known for his tactfulness towards the Roman Empire-backed Herodian dynasty that conquered Judea and supplanted the Hashmoneans in 37 BCE. Josephus later recounted his growing up in a privileged, wealthy lifestyle that included a full education.

At 16, Josephus apparently traveled on a 3-year long spiritual trek in the wilderness with a member of an ascetic Jewish sect. After his return to Jerusalem, he joined the Pharisees – another Jewish faction that, crucially, had no issue with non-Jewish rule of the Holy Land as long as they could practice their religion. On this point, as with many more to come, there exists much scholarly speculation as to whether Josephus actually believed in Pharisee dogma – or merely associated himself with the group as an opportunistic move in anticipation of what he may have considered an inevitable end: the defeat of Jewish revolt against Roman rule of Judea.

Despite overthrowing Judea’s Jewish kingdom 60 years earlier, the Roman regime still fought to consolidate their power against ongoing, if scattered, Jewish rebellions. The hostilities increased, and in his early twenties Josephus traveled to Rome to negotiate with Emperor Nero for the release and return of several captured Kohanim. While Josephus succeeded in his mission there, the Roman culture and sophistication he encountered apparently deeply impressed him – as did the Empire’s military might.

He returned to Jerusalem on the eve of the First Jewish War (66-70 CE), a general Jewish revolt across Judea led by the nationalist and militaristic Zealots who set up a revolutionary government. Josephus – a self-proclaimed moderate, at least in his memoirs –argued for conciliation with Roman forces. One could suggest that one or several factors motivated his stance: his alleged Pharisee beliefs, or his knowledge of Rome’s armed forces, or his elite background. However, in this instance the most logical explanation might again be simple expediency, which also might explain his subsequent actions.

When the Zealots achieved an early War victory in overrunning Jerusalem’s Roman garrison, Josephus pragmatically aligned himself with them. They appointed him their military commander in the Galilee region, although he still inclined towards conciliation with the Empire. His outlook conflicted with that of John of Giscala, a Galilean who had organized a private militia of peasants. Josephus and John wasted considerable time fighting for control of the rebel operations while the forces of Roman general – and future emperor – Vespasian prepared to attack. While Josephus later wrote that he assumed sole leadership of the Galilean rebels, his newfound status became a moot point.

In 67 CE, Vespasian’s army overwhelmingly destroyed most of the Galilean resistance within a few months. In his memoirs, Josephus recalled the Romans had him and around 40 fellow Jews under siege. Rather than surrender, the rebels chose to draw lots to determine the man who would kill the others and then commit suicide. Josephus claimed pure luck or divine intervention allowed him to ‘win’ this draw; whatever the true circumstances, he instead surrendered. Brought before Vespasian, he apparently avoided execution by yet another expedient action: predicting the former’s ascension as Emperor. This impressed Vespasian enough to spare the captured general’s life.

Josephus spent the next two years imprisoned in a Roman camp, while his forecast gained credibility after Nero’s death in 68 CE. The following year, Vespasian’s troops proclaimed him Emperor – and he gratefully freed Josephus. In turn, Josephus proclaimed allegiance to the Empire, adopting Vespasian’s family name Flavius as his own.

By 70 CE, Josephus joined the Roman forces under the command of Titus, Vespasian’s son and eventual successor as Emperor, as they began the War’s final battle: the siege of Jerusalem. Over 7 months of brutal fighting, Josephus attempted to act as a mediator between the Empire and the rebels, but his history of shifting alliances led both sides to mistrust him. When Jerusalem fell to the Empire, Josephus went to Rome where, granted full citizenship and a pension, he spent the rest of his life devoted to his literary pursuits. Besides a Spanish translation (1536) of his Jewish War, our collection includes a Latin translation of Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews from 1481, making it our earliest-dated item.

-

Spain’s Juan Cromberger was purportedly born in or near Seville around the start of the 16th century. His parents, Jacobo Cromberger and Comincia de Blanquis, married circa 1499 after the death of Comincia’s husband Meinardo Ungut, a German printer who had employed Jacobo. Jacobo then assumed control of Ungut’s press, also acting as an editor and bookseller there. The couple had two children: Juan and daughter Catalina.

Between 1503 and 1520, Jacobo printed an estimated 300 editions, including a 39-volume series of legislative decrees by Portugal’s King Manuel I, who had personally summoned him to Lisbon. Cromberger’s press, by now a lucrative enterprise, monopolized a large portion of Spain’s book industry. His business and contacts soon extended across Andalusia to include the jewelry trade (which also reached the Americas) and the slave trade – the latter from which he drew slave labor for his press.

By 1525, Juan had already worked alongside Jacobo for several years, and he eventually took control over most of the press’s operations. Juan also married Brigida Maldonado, a daughter of Salamancan booksellers. She convinced both Crombergers to print new books rather than simply reprinting known bestsellers – a risk that later proved highly profitable.

Upon Jacobo’s death in 1528, Juan inherited a vast fortune, his father’s commercial connections and jewelry interests, and part of the press’s stock. His sister Catalina inherited the remainder of the stock; Cromberger bought her out to control the press completely.

Between 1529 and 1540, despite increased competition from other printers, Juan’s profits surpassed that of his late father. One factor may have been that he chose to print fewer high-minded works in Latin, favoring Spanish books with potentially larger sales. Significantly, Cromberger also listed his primary occupation not as a printer but as a “merchant”. That rather innocuous term belies his investments in less-than-savory, if moneymaking, trade with the New World in his family’s established concerns (jewelry, slave trafficking) and newer ventures such as silver mining.

Nevertheless, history memorably and justifiably notes Cromberger’s role in bringing printing to the Americas, namely New Spain (now Mexico). In 1533, his press was considered Seville’s most important, responsible for producing works for the archbishop whose authority extended to the Mexican diocese. When Juan de Zumárraga, New Spain’s first bishop, decided a printing press would assist in his evangelization efforts there, he chose Cromberger to establish it. In turn, Cromberger sent Juan Pablos, an Italian printer, to set it up.

A 1539 contract committed the press to print 3,000 pages per day over a 10-year period under the Cromberger imprint, although Pablos would subsequently own it. Cromberger financed it entirely: its initial funding; Pablos’ journey to Mexico alongside his wife, an additional employee, and a slave; and all the press supplies required. In return, Cromberger obtained a monopoly on the printing and distribution of books in New Spain. This press produced Breve y más compendiosa doctrina Christiana en lengua Mexicana y Castellana (1539): the first book ever printed in the Western Hemisphere.

Sadly, Juan himself barely benefited from his new monopoly, dying in 1540. In Seville, his wife Brígida continued to run the press while managing the New Spain outpost, until her son took over the entire business 6 years later. She never remarried.

Brigida’s grandson Jácome became the Cromberger printing dynasty’s last practitioner. Like his grandfather, Jácome also married a Salamancan printer’s daughter, but fate proved less kind to them: many publications produced during his tenure eventually made the Catholic Church’s Index of Prohibited Books. As a result, the Cromberger family fortune dried up; by 1557, the press finally closed. The same year, Jácome left Spain for the West Indies, dying shortly thereafter.

-

In 1536, barely a half-century after Venice’s Rinaldo de Novimagio published the JPL’s copy of Josephus’s Antiquities of The Jews, Seville’s Juan Cromberger published our copy of the Spanish translation of De Bello Judaico. One can readily discover tangible improvements in the development of printing techniques between these two books, to say nothing about the strides taken in the 80 years between Gutenberg’s first printing and Cromberger’s efforts.

Our copy measures 27.5 x 20 x 3 cm. It still wears its original bindings of stiff beige leather that is soft to the touch, somewhat worn but with little damage, although there is a dark brown smudge on the front cover’s upper left-hand corner. On the spine, “Historia de Flavio Josephus” is hand-written in dark ink, although the last half of “Josephus” disappears beneath “Sevilla, 1536” on the spine’s bottom inch. “825” appears on the spine’s top, beneath a mostly-faded symbol that appears to have been a letter — perhaps a “K” – enclosed in a “C” or “G”. Along the spine’s top and bottom stitching that has worn through the leather, minor tearing is visible.

On opening the book, we see “C. Sevilla 1536” in ink, hand-written in a similar fashion to the spine inscriptions, in the pastedown’s upper left-hand corner. Beneath this, in pencil, is “E. 3” [?], although a line has been drawn through it, with a larger “S-1” beside it. Above this, someone evidently inscribed another text portion right along the pastedown’s top center at some point; but its later erasure apparently tore away part of the pastedown. The leather binding has come apart from the pages, though it remains attached at the bottom by the end-band’s stitching. The end-page recto is blank, except for large figures at the top: “6-2=926926”, written in pencil. A watermark is clearly visible in the page center. A tilted crown sits atop an ornate frame, topped by a cross, within which the letters “I H S” appear. Beneath this are the letters “PERRS”. This watermark does not appear elsewhere in the book. Instead, the watermark that appears within the book depicts a hand topped by a star.

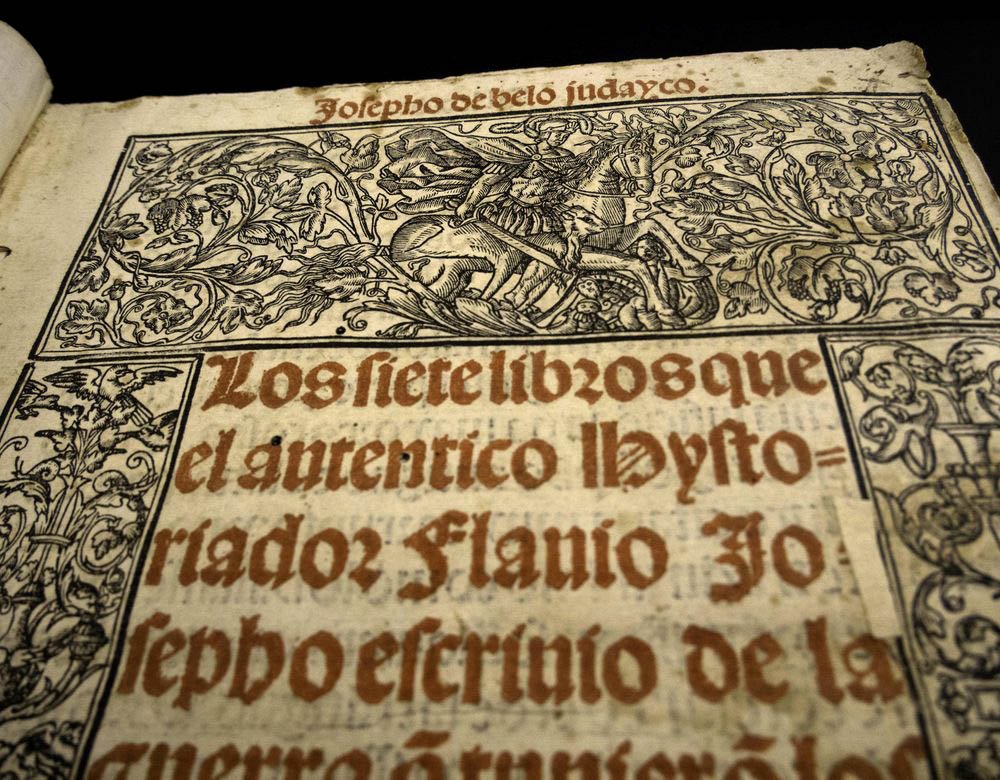

The title page contains elaborately illustrated frames. In the top frame, a knight rides on horseback, sword in hand. The side frames of fountains and trophies feature cherubs as decorations: one trophy contains the letters “S.M.” In the bottom frame, cherubs hold up a coat of arms, containing a globus cruciger within which “I C” has been inscribed. Within these frames, red text identifies the author and the work, with a black-inked date of printing in Roman numerals. The title, in red ink, appears just above the top frame. The title page recto contains a note to the reader, containing the names of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. The following page verso begins the prologue to the text proper.

Each section begins with an illustrated initial, which appears printed rather than hand-drawn, as some are identical without variations. This is perhaps the biggest difference between this book and our 1481 copy of the Antiquities, where blank spaces indicate an intent for an illuminator to add them by hand. Another difference between the two: no marginalia is present, unlike the heavily annotated Antiquities. In fact, the only handwriting appears on the last page, where text in now-fading ink seems meant to replace text lost to water damage.

This book, like the Antiquities, comprises gatherings of eight, folio-sized pages; the text appears in columns of two instead of the single, full page-spanning columns commonly in use just a few years hence.

The foliated, cloth pages show minimal damage throughout – primarily bug damage along the spine, although there are a few torn pages. There are no catchwords, but the gatherings are indicated in the lower right hand corner. The colophon appears at the end of the work, along with a text paragraph explaining the work and providing the printer’s name, place and date of publication. After the colophon, a table appears at the book’s end, detailing the fact that 7 books comprise the entire work, each divided into chapters, with the folio on which each chapter starts indicated.