Hamishah Humshe Torah...bi-leshon Ashkenaz

(Amsterdam : Uri Phoebus Halevi, 1678)

-

(…and the Scandal)

The profitability of Amsterdam printer Uri Phoebus Halevi’s Yiddish books prompted his interest in producing a Yiddish Bible to appeal to his primary audience in Poland. He fairly quickly secured financing from a Christian and obtained approval from Poland Jewry’s central body of authority – the Council of Four Lands – for his translation. The Council provided Halevi with Germans Yekutiel Blitz – a translator and proof-reader – and proof-reader Joseph Witzenhausen. Witzenhausen was already a famous Hebrew typesetter, known for his work on a Yiddish version of the Arthurian legends (1671). However, problems soon plagued Halevi’s project. The Dutch War (1672-1678) stalled the work, Halevi found himself bankrupt, and he also lost his original Christian backer. However, with the War’s end, Halevi recuperated his fortune, found a new underwriter and hired Sephardic rabbi and expert printer Joseph Athias as his new proof-reader. It appeared that circumstances now favoured the Halevi Yiddish Bible’s creation and publication – instead, they went spectacularly wrong.

Athias, the proof-reader, insisted on always maintaining physical possession of his work. As he worked, he grew increasingly unimpressed with Blitz’s translations. For unknown reasons, Athias came to consider himself, along with Halevi’s new underwriter, as the translations’ rightful owner despite Halevi’s financing and Blitz doing the bulk of them. Athias had completed slightly less than ½ the work when he absconded with over 50,000 sheets of translation, including all of Blitz’ work up until Chapter 21 of Exodus. Athias then successfully applied to the Amsterdam authorities for permission to print his own Yiddish bible, using the stolen sheets as proof of ‘his’ upcoming book’s state of advanced production. They granted him a 15-year exclusive publication right, and Athias immediately hired Witzenhausen – the original proof-reader – to complete the translation.

Halevi contested but failed to reverse the authorities’ decision, and so ended up competing with a former employee possessing most of the texts for which Halevi had hired him. Despite this delay, including the necessity to print the Pentateuch sections last due to Athias and Witzenhausen’s defection and theft, Halevi and Blitz completed their translation before Athias did. Their Yiddish Bible – the first ever – appeared in 1678. Athias and Witzenhausen’s version went to press the following year.

Blitz and Witzenhausen both had no scholarly education in Hebrew grammar, no access to Hebrew-Yiddish dictionaries or Hebrew grammars, and did not engage Hebrew grammarians to work with them. As a result, both Yiddish Bibles contain innumerable translation errors. In particular, Blitz’s Yiddish evinces demonstrable influences of Christian translations of the Old Testament in Dutch and German, both languages familiar to Blitz.

Ironically, neither Bible met with any commercial success, with the majority of copies sold only at auction. Although their audience of Yiddish readers needed a Bible in their vernacular, they also felt it somewhat lacking if a holy book did not include the original Hebrew text. A century later, the sales of Mendelssohn’s Judaeo-German Bible would prove such an inclusion could help avoid the Yiddish Bibles’ fate in the marketplace.

-

Little is known about Wittmund (Germany)-born Yekutiel ben Isaac Blitz (c.1625-1684), other than his arrival in Amsterdam at least by late 1670, where he was employed as a proof-reader at Halevi’s press.

-

Amsterdam-born Uri Phoebus Halevi (1625-1715) – the grandson of the first Amsterdam Spanish-Portuguese Jewish community rabbi and son of its synagogue’s first cantor – printed from 1658 to 1689.

He had first worked as a typesetter for Immanuel Benveniste, in whose establishment he printed Pappenheim’s edition of the “Mishle Ḥakamim” in 1656.

In 1660 he briefly joined a new Polish Ashkenazi congregation that had splintered from the existing, mostly German Jewish Ashkenazi one in Amsterdam, but by 1673 Halevi had rejoined that older group once the Polish faction re-merged with it.

He was a member of Amsterdam’s bookseller, printer, and bookbinder guild under the name Phylips Levi. In 1669, he published the Tsene-rene, a Yiddish adaptation of Hebrew Bible portions considered appropriate for women which became one of his best-selling books. He died in Amsterdam.

-

The nucleus of Amsterdam’s Jewish community arose from out of the mass Jewish exodus from Spain and Portugal into North Africa, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire. As Jews in these areas often faced religious restrictions, prohibitions and far worse persecutions, many became disenfranchised from their ancestral faith and its Hebrew language yet still encountered religious discrimination. In turn, they and many descendants immigrated to Amsterdam, a relatively tolerant city.

Once there, however, they realized that while free to openly practice Judaism, they would also require a great deal of guidance to relearn it. To meet this need, they initially used many religious books produced in and imported from Venice, as well as reprints from Dutch presses – all in Spanish and Portuguese. By 1626, Rabbi Manasseh ben Israel founded Amsterdam’s first Hebrew printing press. On January 1st, 1627, it produced the first Hebrew prayer book ever published there – a harbinger of what became one of the 17th and 18th centuries’ most robust Jewish centres of printing.

Within a few years, Amsterdam’s Portuguese-Jewish community had grown: they established no less than 3 Sephardic congregations, along with their accompanying educational institutions, elder care organizations, and cemeteries. In 1639, the congregations merged and the resulting unified, well-structured group emerged as European Jewry’s largest and wealthiest. However, by the mid-1600s Ashkenazi immigrants from Germany and Poland founded their own, larger congregation; the synagogue they constructed in 1671 momentarily stood as Amsterdam’s largest until the Portuguese cohort completed its own that same year. That Amsterdam’s ever-growing Ashkenazi and Sephardi population could both unreservedly worship as Jews and build and fortify such institutions – all while engaging in the commercial life of the city as a whole – points to their quality of life being significantly improved as compared to that of Jews in their former homelands.

The late 1600s saw an explosion in the number of Amsterdam’s Hebrew presses serving the local Jewish community’s desire for books in Spanish, Portuguese, Hebrew, and Yiddish; a strong export trade also emerged. Over the next 3 centuries, more than 100 Jewish presses remained active, including renowned names like Athias, Proops, and Van Embden.

Though their most lucrative books were Hebrew ones, they also printed Yiddish titles to cater to what was at first a niche market. The Yiddish printing industry that had sprung up in the early 1500s in Northern Italy, Poland and Germany had collapsed after a few decades: Ashkenazim in Italy favoured Italian, and political troubles led Polish and German authorities to shut down all Yiddish-related activities. As Ashkenazi Jews flooded Amsterdam, the city’s Hebrew printers spotted opportunity.

From 1644 – when Amsterdam’s Hebrew printers published their first Yiddish books – until the end of the 18th century, the city was Yiddish printing’s nexus for local Jews and those across Central and Eastern Europe. Even though the printers considered Yiddish printing a community service, they also expected it to be profitable despite the relative poverty of most Ashkenazim compared to Sephardim. The books, generally religious or didactic, focused on practicalities rather than luxury as most Amsterdam Ashkenazi Jews could not read Hebrew at a functional level.

During this period, Amsterdam’s Hebrew printing houses published more than 500 Yiddish books, with the Eastern European dialect almost entirely supplanting that of Western Europe. Collectively, these works document Yiddish’s status as a living, breathing language. Though only 3 or 4 different books appeared in any given year they were also frequently reissued, with any changes duly highlighted to prove the reissue worth buying. Such modifications, including adaptations to the Yiddish, mistakes corrected, and textual alterations, indicate that as spoken Yiddish changed, so did written Yiddish. Hayyim Druker – a contemporaneous, long-active Jewish Amsterdam publisher – regarded this as particularly important. He believed that Yiddish books’ practical nature demanded their contents’ constant updating and modernization for their readers – a concept as idealistic as it was convenient for marketing his new editions.

In the 18th century, the combined purchasing power of Amsterdam’s Ashkenazi Jews began increasing along with their economic, if not social, upward mobility. Texts strictly for pleasure began representing a larger proportion of Yiddish books printed. However, according to the late University of Amsterdam Yiddish studies professor Shlomo Berger, the overall number of Ashkenazi Jews who could afford such items – which had become a status symbol – remained small, and domestic libraries emerged. A small group of readers would purchase the books, then loan them to a larger, secondary circle of readers: the JPL’s roots, of course, have similar origins.

Still, those more affluent Ashkenazi Jews in Amsterdam helped fuel, throughout Europe, a demand for Yiddish books printed in Amsterdam: as more of them could afford better books, the printers responded by lavishing far greater care and preparation on their work than ever. Although these printers still relied on a well-worn “Ashkenazi cursive” script, they began using larger margins, more diligent proofreading and careful typesetting. These books became so popular and desired, with a reputation for being the best-produced books available, that printers elsewhere took to subterfuge. They emblazoned their title pages with the word “Amsterdam” in prominent type size, thus fooling buyers into believing their books were printed there – while simultaneously preceding it with the phrase “In the style of” in smaller type, or printing the book’s actual place of publication in similarly smaller print.

-

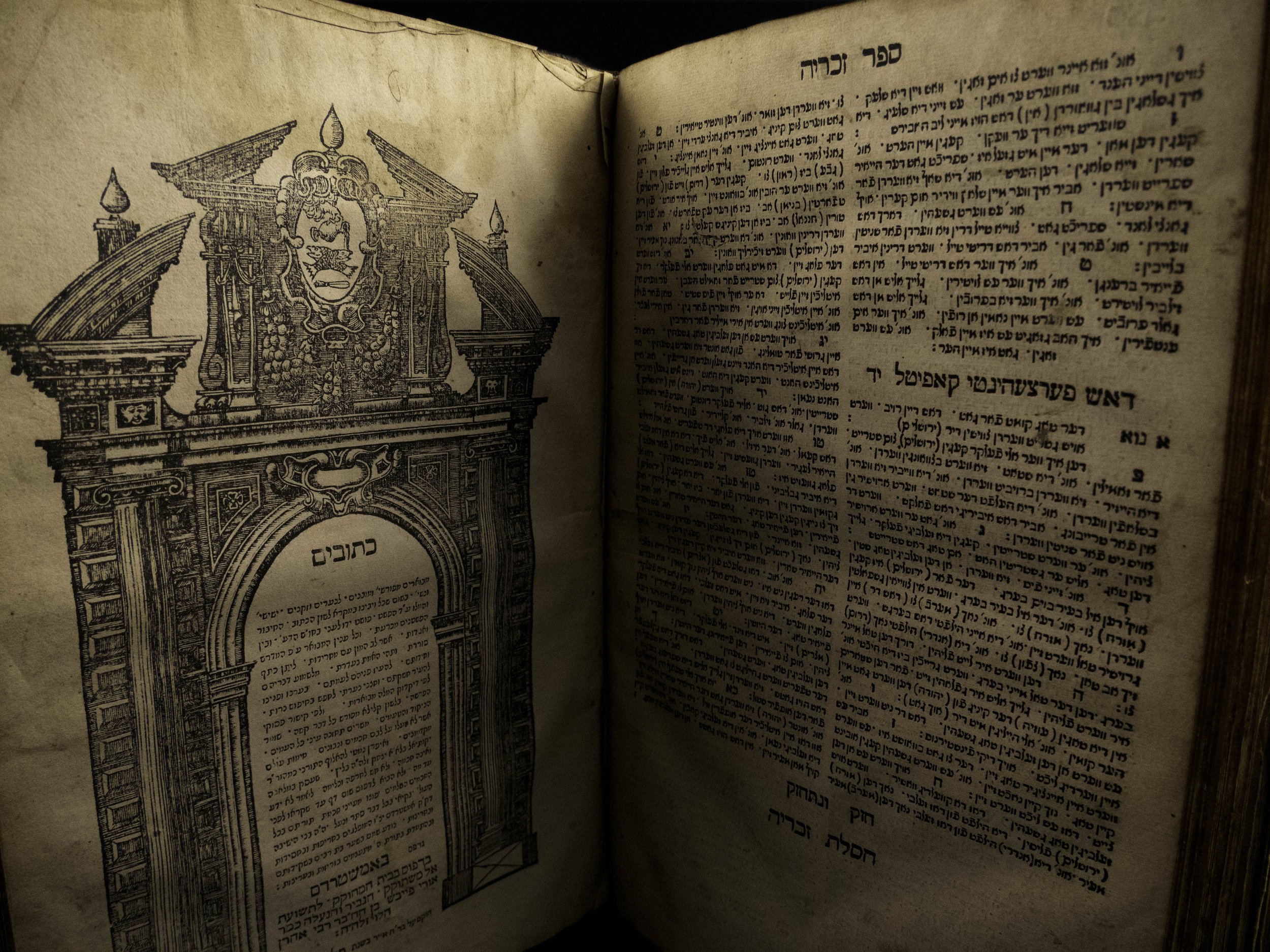

Our library’s copy is one of just 6000 published in the first – and only – Amsterdam 1678 print run. Unfortunately absent: the intricately illustrated title page. Had this not been the case, it would particularly show how this edition deviated from previous Judaeo-German bibles. Those generally contained a few, small wood-cut illustrations, and only included Yiddish (or pre-Yiddish) glosses intended to assist Yiddish speakers in understanding the Hebrew text. It also would demonstrate the influence of Christian printing practices, which had spread from Germany to Amsterdam, upon Jewish books. The use of beautiful illustrations in bibles – especially Luther Bibles – and theological works seeped into Jewish Enlightenment-era printing, again primarily with Hebrew bibles. Other than the Witzenhausen Bible, the Blitz Bible’s ornate title page – unprecedented in a Yiddish work – had no comparison in this time period. Abraham bar Jacob – a convert to Judaism – designed it, his best-known work. However, the design actually only achieved fame when it was used for the iconic Amsterdam Haggadah of 1695.

Our copy, instead, opens on Blitz’s single-page preface defending his translation. As with similar works, this justification – usually required for Jewish authorities’ consent for a translation – defers to the oral Torah tradition, reassures readers of the translation’s fidelity to the Hebrew Torah text, and reminds them that the translator simply intends to make that text accessible to them. Blitz focuses on translation as one of the simanim – signs that help find meaning in the written Torah. To legitimize his work, he also relies heavily on rabbinical texts, repeatedly quoting leading Spanish rabbi Joseph Albo.

The Library likely acquired the book sometime after December 1975 from Michał Łuczak (1932-2007), a Polish journalist and Solidarność trade-union member who was imprisoned between 1981-82 for investigative historical reporting on the 1956 uprising against the Polish government. Łuczak had originally written to Library and Archives Canada about the book ; LAC had passed along his letter to the JPL.