korban pesah

(Livorno : Shelomoh Bilforti ve-havro, 1837)

-

Safed-born Rabbi Hayyim Amram (c. 1759-1825), Korban’s author, hailed from a prominent family of Torah scholars. At age 7, he travelled to Damascus to study in the wealthy Farhi family’s bet midrash, home to the city’s best Jewish students. Over the next 4 decades, his academic renown led him to become its head, as well as a teacher and judge in Damascus’s bet din (Jewish rabbinical court). During these years, he wrote most of his works, becoming proficient in Kabbalah as well. In 1805, he returned to Safed, and after a brief return to Damascus, subsequently settled in Alexandria.

His son Natan (c.1790-c.1870) edited Korban for publication. Natan studied at the Farhi yeshiva, moving to Safed in 1805 along with his father. After his father’s death, he served as a rabbi in Tiberias and Hebron, where the 1834 Arab revolt against Ottoman rule resulted in the killing of Jews. Natan then toured Europe to raise funds for Hebron’s Jewish community. Accused of misappropriating the proceeds, he wrote a pamphlet defending his activities, then moved to Livorno before finally travelling to Alexandria in 1851. There, he eventually served as its chief Rabbi. Upon his death, he was given a state funeral.

-

“It is enough to have had the determination”. In 21st century Livorno, this publisher’s motto definitely reflects its namesake family’s history, which includes the printing of our copy of this book.

Livorno-born Shlomeh Bilforte (1804-1869), usually known as Solomon Belforte, was the son of Joseph Belfort, a printer who had funded his own publication of a Hebrew book of penitential prayers. By age 16, Solomon began working with Livorno’s Tubiana typographers. They worked together on at least 4 prayer books for Rabbi Jacob Tubiana’s press, which include Shlomeh’s name among their credits. In 1834, he started his own press – Belfort & Compagnia – with the help of brothers Moise and Israel Palagi. They purchased their type at Pisa’s Villa foundry, and set up two presses on one floor of a Livornesi palace. The firm’s initial license limited it solely to Hebrew works, but within nine years and after repeated petitions to the authorities, they succeeded in obtaining provisional approval to print in Italian. Two years later, that licence became permanent, and a further 3 years later, ecclesiastical censorship ended completely and freed the press to print as they wished.

In 1845 Shlomeh’s son Giuseppe joined the company. A schoolmaster, with little training as a typographer, he worked alongside his father until Shlomeh’s death. Giuseppe then took over the press, renaming it Salomone Belfort & Compagnia. Giuseppe’s son Giulio repeated the pattern, with yet another corporate re-branding; however, it was his other innovations that truly led the firm’s dominance in Hebrew printing for nearly a century, from the 1880s onward.

He first bought out the Palagi brothers’ share of press equipment and book stock; then introduced colour printing and graphic arts; and, after traveling to Germany to learn stereotype printing, he opened the company’s first bookstore. The press’s Hebrew publications soon acknowledged this new venture, as their title pages now included ”Madpisim u-mokhre sefarim” – printers and booksellers. As well, the range of Belforte titles grew: they added school texts, Italian-German dictionaries, and novels with both black-and-white and color illustrations. In 1899, Giulio expanded the business further, by opening a book and paper shop which also housed one of Livorno’s first telephones.

Before the outbreak of World War I, Giulio’s 3 sons – Aldo Luigi, Gino, and Guido – worked for the company, but were conscripted into Italian military service. Their mother Emma Castelli temporarily assumed the reins as Giulio’s health failed. With the war’s end, Aldo Luigi assumed overall control of the firm. He broadened its flagship bookstore’s offerings: hosting events featuring artists and intellectuals, selling English and French foreign titles, and adding reference books, maps, and globes to its inventory. He also inaugurated new stores in Lucca and Viareggio. At the same time, his brother Gino developed another avenue for the family business, opening one of Italy’s first art galleries in 1921. As for the company press, their sibling Guido seems most involved. He updated its printing equipment, and continued printing works of and on theatre, literature, religion, and Hebrew culture, as well as schoolbooks and children’s works.

In 1924, the Belforte conglomerate celebrated its 90th anniversary with a catalogue of their Hebrew printing that celebrated their prayer books’ global appeal, being sought out by sellers and readers from North Africa, the Levant, Istanbul, Egypt, India, and the United States. The press now also printed those items in Ladino, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Judeo-Italian, and Judeo-Spanish. For their centennial, the Belfortes produced a beautiful publication that drew praise from the National Fascist Confederacy of Printing – but circumstances soon took a turn for the worse.

Italy’s King Vittorio Emanuele III and Prime Minister Benito Mussolini had jointly nominated Guido for a national order of merit for his business success. However, by December 1938 Mussolini’s government had passed racial laws forcing the Belfortes to splinter their companies and relinquish control of them to several non-Jewish friends. Yet Guido and Gino continued printing, having managed to move one press despite the confiscation of the firm’s equipment. They opened a bookstore in Castiglioncello, where non-Jewish employees and friends sheltered them in the surrounding countryside. Unfortunately, upon their post-World War II return to Livorno, Guido and Gino discovered their flagship bookstore had been bombed, and presses gone. Even had these been left intact, the market for their Hebrew publications disintegrated in the wake of the emigration of many Italian Jews to Israel.

Nevertheless, the Belfortes remained undaunted. Gino oversaw the printing of the Telegrafo, which included a daily run of 200,000 copies of the American armed forces’ Stars and Stripes newspaper for their soldiers based in Italy. After Guido’s death in 1950 his son and son-in-law, along with Aldo Luigi’s son and son-in-law, regained control of the family’s press and publishing businesses. Sadly, in 1961 they went bankrupt, compelling them to sell their Hebrew types and copyrights to a Tel Aviv publisher.

As for the Belfortes’ bookselling, they had kept their namesake bookstore alive in various locations after World War II. By 1964, its original building had been restored and the Belfortes eventually reopened there with some success. It also housed a revived family imprint spearheaded by Aldo Luigi’s son-in-law. While the bookstore permanently closed in 2017/8, Salomone Belforte S.a.s. remains an active entity. As of 2019, it still publishes Italian-language books on Livorno’s history, culture, and celebrities, as well as psychology, pedagogy, contemporary art and linguistics.

-

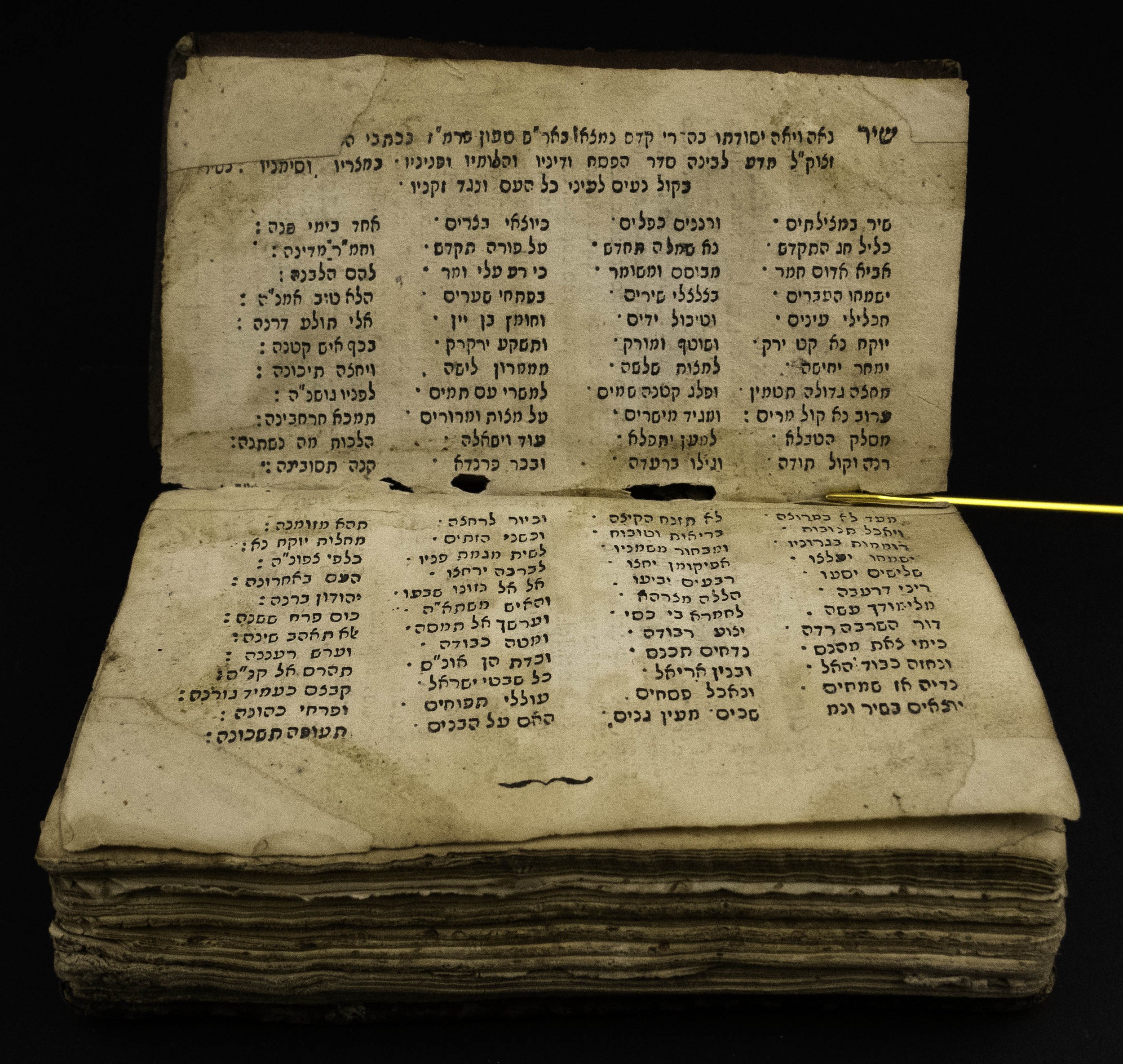

Our copy of this commentary on the Passover Hagadah was printed in 1837 by Shlomeh Bilforte. A tiny book, compared to others in our collection, it measures only 13.5 x 7.5 x 3 cm. Bound in brown leather, it does not appear to have been rebound. Four leather straps, along with twine stitching, secure the spine – although its top and bottom are fully exposed due to the degrading leather. As a result, they have been re-stitched with red and yellow thread. An ornate diamond-shaped design is tooled into the front and back covers’ leather, the front one mostly obscured by damage to the leather. Both covers’ edges show a considerable amount of fading and wear.

Opening the book, the title page’s unusual layout confounds a reader’s expectations: cramped and bereft of decoration, it reflects the copy’s miniature dimensions. The title, at top, greatly resembles a page heading. Like the rest of the book, it features both Rashi and Ashkenazi block print scripts, with Rashi script predominating. The inside front cover includes the remains of an ex libris plate, at least partly blue and gold-coloured.

On the book’s back cover — which in fact is the book’s front cover, as Hebrew text is written from right to left — an owner affixed another, interesting ex libris plate. Vividly green-coloured, with Arabic text at top and Hebrew text along the bottom, its central crest reads in Spanish, “Glassford y Cia – Gibraltar”. Its quadrilingual design appropriately reflects Gibraltar’s history as a trade centre for English, Spanish, Jewish and Arabic-speakers. However, its back cover placement and inverted orientation suggest the book’s owner either did not read Hebrew, or was accustomed to opening books from left to right as with Latin or Cyrillic texts.

Its owner was likely either of two 19th-century Gibraltar natives and successful merchants. William Glassford and his eponymous son descended from John Glassford, the richest of Glasgow’s 18th-century “Tobacco Lords” whose Scottish mercantile and shipping empire once spanned Virginia’s tobacco fields to Gibraltar’s shores.

By the 1870s, William Sr. had retired to England, while his son participated in and even chaired many Gibraltarian commercial and social institutions. Among them, William Jr. served as a deputy-governor of its civil hospital, representing the Protestant population. Jews also served on these organizations’ boards – in fact, they then comprised 1/3 of Gibraltar’s citizenry. They also comprised most of Gibraltar’s commercial class. It seems quite possible, therefore, that William Jr. might have obtained this book from a Jewish social or business acquaintance.

Despite its disintegrating spine, our copy’s pages evince little damage other than significant discoloring. Regular, even margins – although small, to accommodate the book’s dimensions – demonstrate the printing’s good quality. After nearly 200 years since its appearance, our copy’s typeface remains clear, and its ink shows no signs of fading. Near the book’s middle, a few sections show bookworm damage along the spine, which perhaps helps explain the spine’s fragility.