Sefer Luhot 'Edut

(Altona [Germany] : Aaron ben Elijah ha-Kohen, 1755)

-

The Emden-Eybeschütz Controversy And The Sabbateans

In 1648, 22-year old Izmir native Sabbatai Zevi proclaimed himself the Jewish messiah. Some 30 years later, despite his alleged conversion to Islam shortly before his death and the disillusionment this created among many of Europe’s Jews, thousands of them still secretly believed it and practiced his teachings. The resulting internecine conflicts exploded into a dramatic series of controversies. One of the most famous of these involved rabbis Jacob Emden and Jonathan Eybeschütz of Altona, in present-day Germany.

Long-standing roots formed the controversy’s basis. In 1725, Eybeschütz – then an up-and-coming rabbi in Prague — was rumored to be the Sabbatean author of Va-Avo’ ha-Yom el ha-‘Ayin, an anonymous work synthesizing various Kabalistic practices and schools of thought, including Sabbatean approaches to Kabbalistic literature. Its high quality of scholarship drew suspicion on him. Although he later signed an excommunication order prepared by Prague’s rabbis and scholars banning Sabbateanism — effectively alienating the growing Sabbatean communities of Hungary, Moravia and Bohemia — Eybeschütz hardly denied he authored Va-Avo’. As well, his leniency in allowing excommunicated Sabbateans to repent lent further credence to those suspecting his rumoured beliefs.

The controversy accelerated with his 1751 election as chief rabbi of the “3 Communities” (Altona, Hamburg and Wandsbeck), a position that Emden coveted. Emden believed him to have Sabbatean leanings based on amulet texts Eybeschütz wrote to protect women during childbirth. Accusations soon split Altona’s Jews into two camps, with Emden forced to flee to Amsterdam. There, as a printer by trade, he prepared a series of written attacks on Eybeschütz. On his return to Altona, Emden published no fewer than 24 pamphlets condemning him. However, he frequently obscured or omitted their authorship or place of publication.

The dispute reached its zenith (or nadir) in 1752 when Emden and Eybeschütz excommunicated each other. This drew the attention of prominent European rabbis, including Ezekiel Landau (Prague) and Pinchas Katzenellenbogen (Boskowitz), as well as Altona’s Danish king. The latter banned the printing of polemics in an attempt to stifle the uproar. Nevertheless, this obvious barrier to Emden’s own press did not prevent the writing and exchange of letters prolonging the situation.

For one, Rabbi Landau’s missive, addressed to the leaders of Europe’s 7 largest Ashkenazi communities, argued the ongoing, growing distribution and circulation of Sabbatean writings among all Jews was far more concerning than Eybeschütz’s amulets. He also considered Sabbatean-inflected Lurianic Kabbalah’s increasing popularity among scholars as an even greater threat to spiritual communal life. Landau hoped Eybeschütz would compromise by condemning his own writings, thereby clearly disowning the implied stamp of approval of Sabbatean thought from the rabbinic establishment to which Eybeschütz belonged.

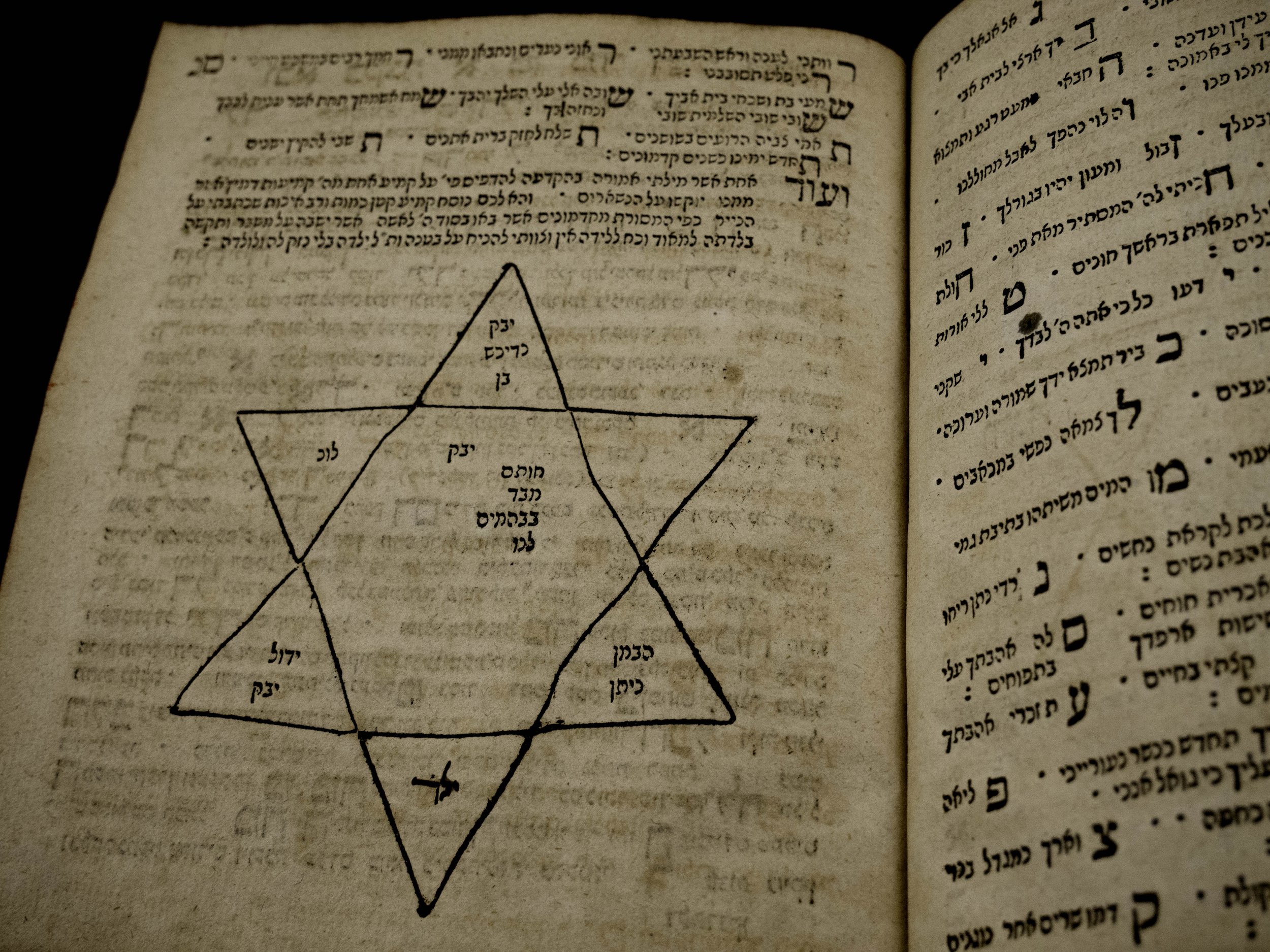

Eybeschütz’s amulet texts, however, remained the controversy’s central issue. In Luhot ‘Edut (“Tablets of Testimony”), he defended himself claiming vision problems and unfamiliarity with Hebrew square printing hindered his handwriting, thereby distorting his intended meaning and inadvertently providing evidence for his opponents. Along with many letters of support to Eybeschütz, part of Rabbi Landau’s letter appears in Luhot, although he and Eybeschütz each later claimed the other utilized only those sections which best supported their own perspective.

While Luhot’s publication effectively quelled the controversy, it was revived in 1760 when some of Eybeschütz’s yeshiva students were exposed as secret Sabbatean practitioners.

-

Kraków-born Jonathan Eybeschütz (1690-1764) was a Czech rabbi’s son, and a child Talmudic prodigy. After his father’s death, he studied under the renowned Czech rabbi, Meir Eisenstadt. After briefly staying in Vienna, he married Elkele Spira, a rabbi’s daughter. After moving to Hamburg, Eybeschütz then settled in Prague in 1700. His preaching there earned him as much renown and fame as his work as head of its yeshiva, where students across Europe vied to study under him. He also obtained permission to print the Talmud, though he was required to remove all passages contradicting Christianity.

Eybeschütz then encountered several career setbacks. In 1722, Prague chief rabbi David Oppenheim closed the yeshiva after Eybeschütz refused to limit student enrollment and charge tuition fees. As well, rumors began circulating about his Sabbateanism, despite his famous 1724 Yom Kippur proclamation denouncing the movement. When Oppenheimer died in 1736, Eybeschütz was passed over as chief rabbi, being instead appointed a dayan (rabbinical court judge).

In 1741, he moved to Metz as its head rabbi. A decade later, Eybeschütz was elected chief rabbi of Altona, Hamburg and Wandsbeck (known as “The 3 Communities”). Eybeschütz bested Altona Rabbi Jacob Emden for the job, which may well have contributed to what became known the Emden-Eybeschütz Controversy. Emden accused Eybeschütz of Sabbatean leanings, based on the apparent contents of handwritten protective amulets the latter had created and given to pregnant women.

Eybeschütz was ultimately exonerated by Europe’s leading rabbis, but in 1760, his youngest son revealed himself as a Sabbatean prophet with links to the Frankist movement. Simultaneously, students of Eybeschütz’ yeshiva were discovered to have Sabbatean ties, and the yeshiva was closed. Four years later, Eybeschütz died in Altona.

Eybeschütz was considered a charismatic, erudite Talmudic and halachic (Jewish law) genius. His 30 books reflect his wide array of knowledge, but the only one that incorporates Sabbatean concepts — and that can be conclusively linked to him — is the anonymously-credited Va-Avo’ ha-Yom el ha-‘Ayin , unpublished in his lifetime. Conjecture exists that Eybeschütz authored several other Sabbatean works anonymously.

His descendants include his granddaughter Lucie Domeier, a poet and writer; Peter Drucker, a leading 20th-century business management scholar and consultant; and Chava Rosenfarb, a Yiddish novelist and poet who survived the Holocaust, settled in Montreal, and contributed significantly to the JPL’s cultural programming from the 1960s to the 1990s.

-

Altona’s history of Jewish printing is fraught with intrigues and controversies comparable to those surrounding Luhot’s publication and reception.

In 1708, Moses Joseph Wessely applied and failed to obtain the first printing license in Altona, on behalf of Isaac di Cordova, an established Amsterdam printer. In 1726, Samuel Popert’s application succeeded. A clause in his license stipulated that his product was subject to censorship, as well as the approval of Altona’s chief rabbi Ezekiel Katzenellenbogen. Popert’s press failed, perhaps because of a much more successful unlicensed press in nearby Wandsbeck, which, interestingly, had Katzenellenbogen’s support .

It took until 1732 for Ephraim Heckscher to firmly establish a Hebrew press in Altona. Heckscher belonged to one of the city’s leading families, serving on its rabbinical court and that of Hamburg. However, his press was unlicensed, and he was more a publisher than printer, leaving the actual work to Aaron ben Elijah ha-Kohen, Luhot’s eventual printer. Kohen soon became the sole individual credited as part of Heckscher’s firm, and became a central figure in Altona’s Hebrew printing industry.

In 1743, Jacob Emden applied for a printing license, requesting it be unrestricted. His previous encounter with ha-Kohen colored this demand: Emden had written an attack on Katzenellenbogen that he submitted to ha-Kohen to print. Ha-Kohen then submitted it to Katzenellenbogen himself for approval! Emden’s application was eventually accepted, but under two conditions. The first was his restriction in printing works only in Hebrew; the second, unfortunately, was the very stipulation he wanted to avoid: the chief rabbi’s approval. Still, Emden began publishing, and in an interesting turn of events he hired ha-Kohen.

In 1751, complications for Emden’s press arose with Eybeschütz’s election as the “3 Communities”’s chief rabbi. Altona, of course, was one of those 3; and now Emden was obviously printing nothing but his own works – ones that criticized a chief rabbi of Altona yet again. It’s small wonder why ha-Kohen chose to print Luhot only a few years later.

Ha-Kohen was not the only Altona printing figure connected with Emden. Sometime before 1765, Moses Bonn had apprenticed at Emden’s press, after which he apparently worked in Hamburg and Altona in collaboration with Christian printers and then at his own, unlicensed press. Bonn later printed Eybeschütz’s works.

In 1769, the Altona authorities insinuated that a Hebrew calendar, allegedly produced there, insulted Christian holidays. They held the Jewish community’s leadership responsible, and ordered it to control Hebrew printing. The community leaders insisted any such calendar, if it existed, was produced without their knowledge or consent, but the authorities’ resolution stood. As it turns out, the documentary record indicates no Hebrew calendars were printed in Altona in the 1750s-1760s.

In 1805, under pressure from Altona’s chief rabbi, the Danish authorities banned Moses Bonn’s sons from printing Peter Beer’s Toldot Yisra’el — despite the fact that the Bonns’ license did not stipulate the rabbi had such censorship privileges.

-

This is the very edition printed in Altona instrumental in dispelling the controversy. A slender volume, composed of only 55 numbered leaves, it measures 19 x 16.5 cm, at slightly less than 2.5 cm thickness. It appears to have been rebound with a brown, mottled paper on board, though the front cover shows deterioration in its top and bottom corners. On the leather spine binding “Luchot Edut Eibeshutz 11/50, U.U.C.” is imprinted in fading gilt, indicating its possible provenance from a private collection. This unidentifiable person or institution likely arranged for the final page’s rebinding and patching. The book’s pages are almost uniformly discolored. What minimal annotation exists appears on both the front and back pages: a handwritten “11:50” similar to that on the spine, a faded name ending with “Mielziner”, and on the new front end page, a small pencil and pen inscription. The pages appear to have had red marbling added to the fore-edges, likely after the book was originally printed. The marbling, faded and dirty, shows no discernible pattern.