Mirkevet ha-Mishneh

(Sabbionetta [Italy] : Tobias Foà, 1551)

-

During the 1470s, Portuguese-born rabbi, scholar and diplomat Isaac Abrabanel began composing Mirkevet ha-Mishneh (“Chariot of the Copy”), a Hebrew commentary on Deuteronomy. It would take him until 1496 to complete it in the face of his native country’s political machinations, his expulsion from Spain in the Inquisition’s wake, and his fleeing territorial disputes across various Italian regions. Mirkevet remained unpublished until its first edition appeared in 1551 and it is this edition which is held by the JPL.

Deuteronomy – for the most part, the Prophet Moses’ recapitulation of Jewish laws to the nation of Israel before they re-enter the Holy Land after years of exile – would seem an appropriate book for Abrabanel to examine, given his own recent experiences and that of his contemporaneous fellow Jews. Unfortunately, the effects of those circumstances also frequently colour Mirkevet’s viewpoint – which would almost immediately negatively affect its first appearance in print and subsequent editions.

Each Mirkevet chapter briefly introduces a number of questions – varying from a few to over 40 – which Abrabanel then discusses and attempts to solve. He states that his commentaries rely wholly on the close, philological reading of Deuteronomy’s text and subjects similarly used by his predecessors, especially Rabbi David Kimhi. This approach differed from grammar-based analyses like those of the renowned scholar Rashi, as well as those of then-emerging allegorical and mystical commentators.

Throughout Mirkevet, Abrabanel also compared the Jews and society of his time with that of the Bible. He described Christians as “uncircumcised villains”, “unclean robbers”, and “idol-worshippers of a man-made God” – not to mention viewing Jewish converts to Christianity dimly. Only one of these references seemed aimed at near-contemporaneous Church and secular authorities: “Asmodai, king of the demons” being an apparent slur on Spain’s King Ferdinand. Despite this, upon Mirkevet’s first printing in 1551 Catholic Church figures in Italy could and did easily regard such allusions as highly topical insults. Within a few years, the Church’s confiscation, censorship and burning of Hebrew books soon became widespread throughout Italy, with Mirkevet as one of its victims.

All of Abrabanel’s commentaries on the Pentateuch, incorporating a Church-censored version of Mirkevet, appeared in an omnibus edition in Venice in 1571. That edition served as the model for all future editions, although a new, uncensored version saw light in 2013.

-

Lisbon-born Rabbi Isaac Judah Abrabanel (1437-1508), son of a financier in Portuguese king Alfonso V’s court, grew up with a broad education, allowing him to also author significant Biblical commentaries despite equally significant displacements during much of his life.

Abrabanel succeeded his father in his post and also served as a diplomat, both positions earning him substantial income and political goodwill. He simultaneously launched his literary career: in addition to Zurot ha-Yesodot, a short philosophical essay on the four elements, he wrote his first work of biblical exegesis Ateret Zekenim, a commentary on a challenging section of Exodus. He also began work on Mirkevet ha-Mishneh, a commentary on Deuteronomy, and Mahazeh Shaddai, a treatise on prophecy that he later lost and subsequently reworked on in his later years.

In 1481, however, King Alfonso V died and several Portuguese feudal lords began plotting against his successor, João II. Two years later, the king summoned Abrabanel to appear before him on charges of being a co-conspirator. Instead, Abrabanel fled to Spain; although he managed to transfer a substantial part of his fortune, he left behind his family, his belongings and the uncompleted manuscript of Mirkevet.

In Spain, he again rose to prominence and wealth in Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand’s court, as well as write commentaries on the books of Joshua, Judges and Samuel.

When Isabella and Ferdinand ordered the expulsion of Spain’s Jews in 1492, Abrabanel attempted to persuade them to repeal it – even going so far as to offer them financial compensation. Having failed, he then went to live in Naples where he primarily served King Alfonso II’s regime, again as a financier and diplomat. He managed to complete Rosh Amanah, a dogmatic work structured around Maimonides’ 13 tenets of Judaism, before the French sacked Naples in 1494. Abrabanel subsequently followed the Neapolitan royal family to Messina, remaining there until 1495.

He then travelled to Venetian-held Corfu. There, he began writing his commentaries on Isaiah and the Minor Prophets, and – as he recounted in Mirkevet’s introduction – “God brought to me the commentary I had written… my soul filled with joy and happiness and it said I will add to it and enlarge it…”. Abrabanel had discovered a copy of his abandoned manuscript, perhaps brought to Corfu by other Jewish refugees from Portugal.

Abrabanel then went to Monopoli (Apulia) in 1496, where he expanded, revised and completed Mirkevet, as well as composing commentaries on the Passover Haggadah and on the Mishnah tractate Avot. His other works of the same period express the hopes for redemption which at times explain contemporary events as messianic tribulations.

In 1503 Abrabanel settled at last in Venice. He negotiated a spice trade treaty between the Venetian Senate and the Portuguese kingdom, while finishing commentaries on Jeremiah and Ezekiel, Genesis and Exodus, and Leviticus and Numbers. At his death, he left an incomplete commentary on Maimonides’ Guide For The Perplexed.

Abrabanel repeatedly emphasized his quest for Scripture’s peshat or contextual sense in his Biblical commentaries, similar to those of Nahmanides. Still, his work also reflected a wide-ranging study and knowledge of Jewish and non-Jewish scholars – including some with other doctrinal and theological approaches. For example, Abrabanel acknowledged both his 14th century Jewish predecessor Gersonides and the 4th century Christian scholar Jerome in devising his division of each Bible book into sections. As well, he often incorporated detailed explanations of midrashim into his commentaries to extract maximal insight and meaning from the Biblical word. In addition, his questions about the Bible’s authorship and origins demonstrate a novel approach that implies a humanist sense of historicity on his exegesis. This makes his writings, perhaps, the earliest examples of Renaissance stimulus in works of Hebrew literature composed beyond Italy.

However, Abrabanel also did not hesitate to offer blunt criticism and condemnation of any of these sources as he saw fit. He described Rashi’s overindulgence in midrashic interpretation as “evil and bitter”; displayed ambivalence about philosophically oriented Biblical interpretation as practiced by Maimonides and his successors; and rarely referred to Kabbalistic interpretations.

His exegesis innovated in several ways. He compared Biblical social structures to those in contemporaneous European society, as in Mirkevet. He also utilized Christian interpretations when he felt them correct. Furthermore, his comprehensive introductions to the books of the Prophets reflect the spirit of medieval scholasticism and incipient Renaissance humanism.

Abrabanel’s work garnered lasting academic respect and interest. Many later Jewish scholars, such as 19th-century biblical interpreter Meir Loeb ben Jehiel Michael, closely studied his commentaries as did Christian theologians from the 16th through 18th centuries, some of whom translated excerpts into Latin.

-

In 1551 Rabbi Tobias Lazarus ben Eliezer Foà (c. mid-16th century), a wealthy émigré from Savigliano (Italy), had the good fortune to establish a Hebrew press in a northern Italian region. Within a few years, that territory officially became the pet project of a Mantuan duke, whose background may have provided him a rather tolerant perspective on the Jews who had lived there from at least a century earlier.

Vespasiano I Gonzaga – educated in several languages, history and Italian literature – had also studied the Talmud and Kabbalah, and welcomed and respected Jews and Jewish thought. This certainly aligned with Gonzaga’s intent to make Sabbioneta – his new city-state – a “capital of the mind”. It would become, other than Livorno, the only Italian city ever to forgo establishing a Jewish ghetto.

Gonzaga licensed Foà and his two Jewish partners to operate a Hebrew print shop out of Foà’s home – Sabbioneta’s first press of any kind. The Jewish trio owned the firm; a rarity then, as Christians owned most Hebrew presses. Foà’s partners, rabbis Joseph Shalit ben Jacob Ashkenazi of Padua and Jacob ben Naphtali ha-Kohen of Gazzuolo, had previous printing experience in Mantua. However, within a year of the company’s inaugural book release – the first printed edition of the late rabbi Isaac Abarbanel’s Mirkevet ha-Mishneh – Foà became its principal owner/operator.

Foà’s finances allowed him several luxuries in his press’s hiring and production. When Shalit left the partnership in 1554, Foà recruited noted master printer Cornelius Adelkind, formerly employed by both Daniel Bomberg and Marco Antonio Giustiniani until Venice’s Jewish presses closed in 1553. After two years, Foà fired Adelkind after the latter converted to Christianity. Foà’s son Mordechai Eliezer replaced Adelkind. He also engaged two Christian master printers from Switzerland with knowledge of Latin and Greek. As well, Foà purchased a decorative page frame design from a Christian printer who had overused it for two decades; its attractiveness would prove a signature feature in the Jewish printing market for decades to come. Finally, Foà initiated the trend of printing special copies of books, often on costly parchment, for wealthy patrons to buy.

As a result, his press earned a distinguished reputation for its high-quality output, and he published about 50 titles overall in Sabbioneta. However, due to increasing censorship such as public burnings of the Talmud in the regional diocese, Foà closed the press and sold its equipment in 1559. He reportedly died that same year.

In 1563, when Venice allowed Jews to resume printing Hebrew books, the Foà imprint re-established itself there on a smaller scale. Christian printer Vicenzo Conti eventually took it over, and various Foà family members remained active as printers in Mantua, Padua, Pisa and Amsterdam until the early 19th century.

-

When Gershon Soncino published the first printed edition of the Hebrew Bible in 1488, Jews had already settled in what were still various independent regions of Italy for at least 2 centuries. They generally lived and worked freely under varying, sometimes-lax restrictions from the contemporaneous civil and papal authorities, as exemplified by their handling of Hebrew book printing.

For their part, civil authorities such as in Venice appreciated the income from fees and taxes on printer licenses, bookmaking supplies and book sales. Of course, while their fellow Christian citizens benefited the most, Jews could also derive some income and security from the growing book trade. For example, in 1516 Venice’s Jews – even while forced to move into the newly established Ghetto – could still publish Hebrew books as long as they hired a Christian press for the actual printing.

In addition to these mercantile considerations, many Christian clerics and academics also objected to the Catholic Church’s early, sporadic attempts to interfere with this new industry, as they too wanted access to Hebrew works. Furthermore, the Papacy had no legal authority in Venice or other city-states like Sabbioneta, home to the Hebrew press that first published Mirkevet in 1551. However, it did possess such power within Rome – and the same year that Mirkevet appeared, the Church’s pontiff there resolved a papal court case involving two rival Venetian Christian printers of Hebrew books. His decree led to a sustained, 40-year long attack on the Jewish cultural milieu across Italy. Mirkevet became one of the earliest of its many casualties.

The legal fracas began when Padua’s Rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen shopped his commentary on Maimonides’s Mishneh Torah to Venice’s Hebrew book publishers. The Giustiniani press had no interest, but Rabbi Meir convinced the newer, less-established Bragadin press to print it.

The Bragadin edition’s phenomenal success led Giustiniani to publish an identical version. Rabbi Meir then obtained an authoritative halakhic (Jewish legal) opinion from the influential Rabbi Moses Isserles of Krakow that threatened excommunication for purchasers of Giustiniani’s book. Giustiniani, in turn, appealed to the papal court for a similar ecclesiastical ruling against Bragadin’s edition.

In court, the dispute escalated as the rival sides enlisted apostate Jews to verify the other’s book contained anti-Christian writings. They soon further descended into mutual accusations of printing anti-Church texts – notably in the Talmud. The case attracted Pope Julius III’s attention, and he ordered a further inquisition into the matter.

As the Pope deliberated, Tobias Foà’s press in Sabbioneta opened, with Mirkevet its first book. It came out shortly before Giustiniani, suffering from dwindling sales due to Isserles’ injunction, closed his press in 1552.

The following summer Pope Julius III handed down his ruling, ordering the confiscation and burning of all copies of the Talmud, and many other Hebrew books, located in Rome. This duly occurred, and Hebrew printing ceased there until 1810.

Julius III successfully called on other regions to follow his edict, and until at least the early 17th century, his successors inspired at least four waves of censorship against Hebrew books across Italy. Local and regional civil authorities enacted laws strongly advocated by their Church counterparts, who would then enforce them. In many cities and regions, a local Jewish community council often tried to pre-empt and limit these laws’ impact by practicing self-censorship of those books.

However, Jews often found themselves legally compelled to bring their books to censors, usually Jews recently converted to Christianity with sometimes suspect knowledge of the Hebrew language and Judaism. They and their Church overseers added another variable to the series of papal-approved orders, booklists and implied guidelines that they utilized – all of which frequently changed. Even if one censor returned a ‘properly-censored’ book to its owner, a subsequent censor could order it be returned for further examination. Therefore, that book could be repeatedly subject to further censoring, confiscation or burning; its owner could face both fines and imprisonment. To add insult to injury, those Jewish book owners generally had to pay fees for each censorship process.

This climate of censorship led to both obvious and unexpected results throughout Italy. On the one hand, Bragadin’s press in Venice closed soon after Julius’s decision, as did the other Jewish-run Venetian Hebrew presses. Over the next 10 years, the few solely Venetian Christian owned-and-operated firms still printing Hebrew books produced approximately 30 titles – about the same number as had been printed in 1550 alone. By 1563, with a brief respite of religious and civil restrictions, Jewish printers could officially reopen in Venice, but the city never again dominated the world of Hebrew printing.

On the other hand, many Jewish administrators and employees of these presses had relocated to Italian regions that had not yet fallen under the Pope’s sway. For example, Mirkevet’s printer Foà hired several Venetian Jewish master printers.

Still, the censorship trend eventually extended to once-tolerant places like the diocese of Cremona, which included Sabbioneta. Reportedly, the pressure from Church censors there – including Talmud burnings – led Foà to close his press down and sell it only 8 years after printing Mirkevet. Most probably, those same official censored many copies of books that Foà printed, as evidenced by the visibly blacked-out and cutout portions in a copy of Mirkevet held by the JPL.

-

The Library holds 2 copies of Mirkevet’s first edition, printed in Sabbioneta (Italy) in 1551 by Rabbi Tobias Foà’s press. Both measure 22 x 31 x 3 cm and at first glance share several features, the most prominent being the title page recto’s lavishly illustrated decorative frame.

The frame comprises a classical architectural border of two columns supporting an entablature with an elaborate cornice. The columns themselves rest on square plinths wide enough to each hold a large urn; each urn holds a large garland of intertwined fruits, vegetables, wheat sheaves, palm fronds and foliage that extends upwards to merge with the other garland, over and in front of the entablature. Each plinth’s height almost matches that of the standing figure in front of it: these represent the mythological Mars and Minerva, each holding shields. Within this border, a central plain rectangular frame includes Mirkevet’s printed Hebrew main title statement and author, using Ashkenazi block type. Other miscellaneous details appear in Rashi script; the place of publication follows, again in Ashkenazi block type. Underneath this rectangular frame, a circular wreath – similar to those in the urns – encloses a brief printed Hebrew statement, in Rashi script, that notes the Foà press’s responsibility and the book’s date of publication. The verso contains the work’s statement of approbation.

Interestingly, Foà purchased the decorative frame from Francesco Calvo, a Roman printer of Latin and Italian books active from around 1520 to 1540. Calvo used it extensively throughout his career; he or his press’s liquidators realized it might prove a more valuable asset if sold as a novelty in the emerging Hebrew publishing market, rather than to another Christian printer. As well, Foà probably knew that Renaissance-era Italian Jewry would not be offended by its depiction of non-Jewish figures.

Another feature shared by both copies – the text – is printed in the two columns typical of the era. It includes headings in Ashkenazi block print. Most of the text uses similar print, although the typeface is not as customarily clear as expected. Glossing appears in Rashi script. Each leaf includes Hebrew pagination, along with catchwords on its recto and verso’s bottom left-hand corners.

Both copies’ pages consist of fairly thin cloth paper with vertical chain lines. On most pages a watermark – difficult to make out – appears centred vertically, but slightly offset horizontally, towards the spine. However, a pattern repeats itself: several pages bear watermarks, followed by several absent them. A considerable amount of discoloration consistent with moisture damage mars the page edges, but otherwise they show relatively little pest damage.

Aside from these similarities, each copy has distinctive attributes that indicate just how much circumstances over time affected them along their journey to our collections.

Our first copy’s most prominent and shocking feature must be its numerous instances of censored text passages. On the 2nd leaf’s recto, black ink obscures one text portion and has leaked through the paper to the verso side, with another text portion cut out entirely. Leaf 97’s recto also contains heavily blacked-out text, as does a considerably large section on leaf 110. Like some of these examples, handwritten Hebrew script marginalia near other censored portions also indicate that the censors – whether Jewish community members acting preemptively, or Church officials – had some leeway to substitute Church-accepted text in place of material considered objectionable. Notably, a 1968 scholarly analysis of Mirkevet’s manuscript, as well as other copies of this edition, allows us to verify that several commonly censored text portions remained untouched in our copy. Quite possibly, as per the explanation of Italian censorship of Jewish books included on this web page, this was only due to chance and circumstance.

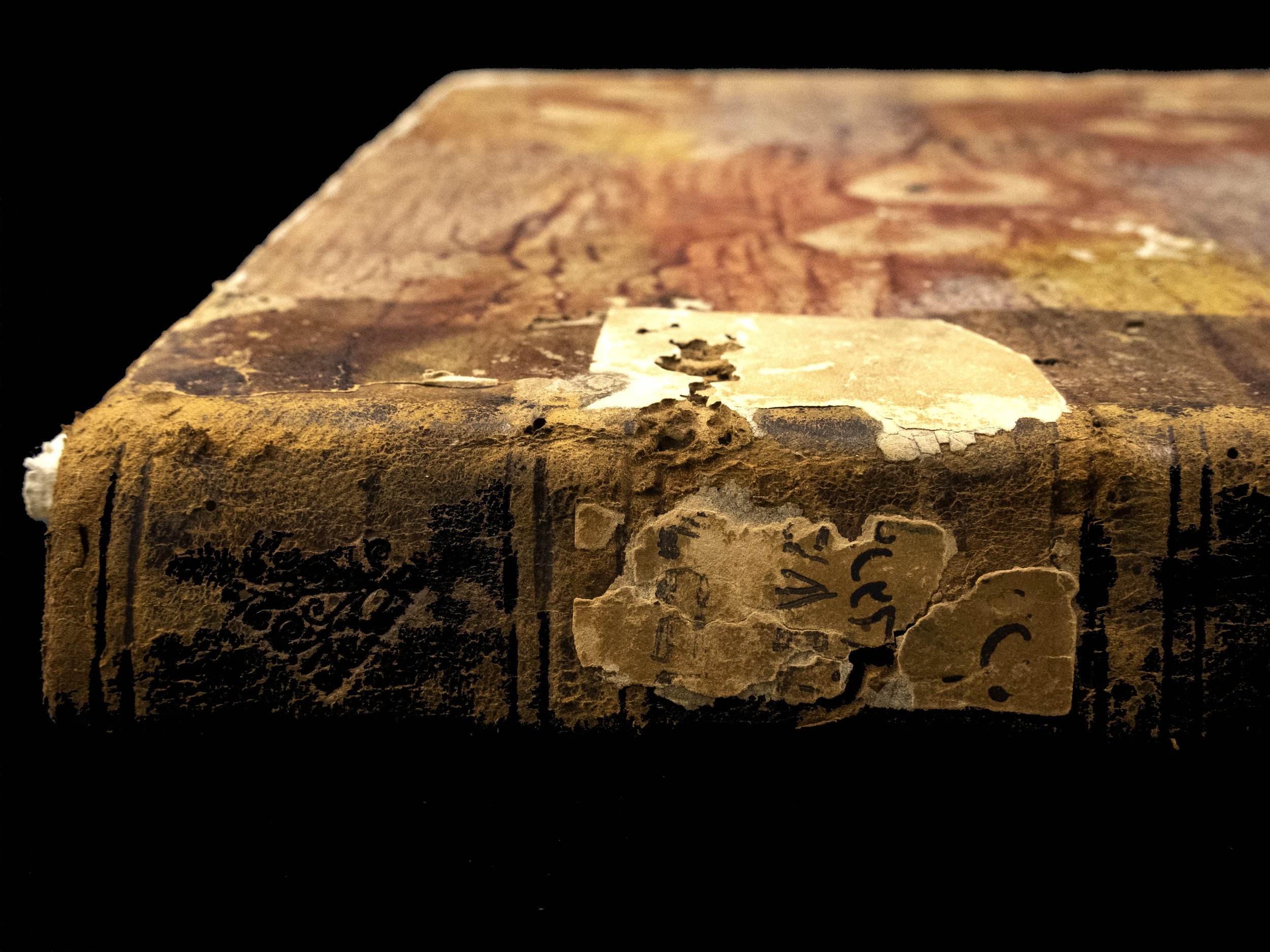

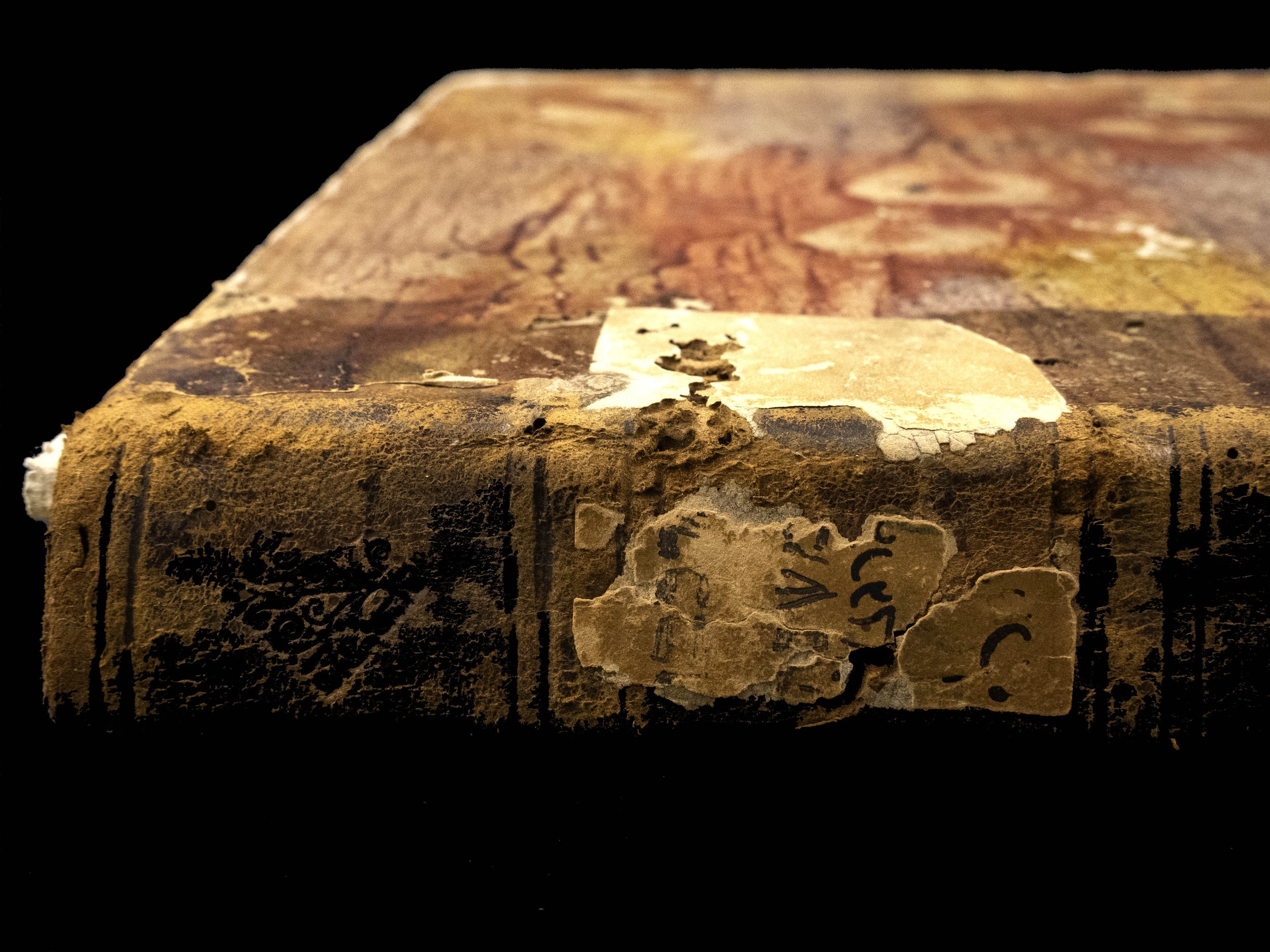

The book’s spine consists of tooled leather, with decorative diamonds in all six of the cases marked out by the spine ridges. On the spine’s top, the remnants of a sticker display handwritten Hebrew portions of the book’s title and author’s name. A similar sticker at the bottom only shows an inked “394”, most probably a partial call or shelf-listing number likely indicating another library once held this copy.

The cover, most certainly not the original, consists of thin paper wrapped around boards and pasted over the spine’s edges. The paper itself appears to be hand painted in purple, yellow and red. The cover assembly suggests the spine remained from a previous binding or was taken from another book entirely. The binding has detached entirely along the spine, revealing the sewn binding whose ridges do not line up with the spine’s tooled lines which generally followed the sewn spine ridges.

As well, the copy’s pastedowns and its two initial end pages are not part of the original work, though these pages bear the JPL’s early-20th century unilingual Yiddish book stamp, in purple ink, and the original end page is not intact.

Upon opening the book, its largely intact title page exhibits but a few small tears. By comparison, most of its pages are somewhat detached from the binding. Leaves 127 to the book’s end are absent, replaced by handwritten ones in a small cursive Hebrew script, except for the final index pages whose last verso includes the Foà press’s printer’s mark. From the above-mentioned 1968 study, one can reasonably conclude these handwritten pages probably substituted for damaged or lost pages – rather than censored ones.

Our second copy has been rebound, perhaps twice. Its cover consists of a brown half-cloth binding over a slightly darker brown leather cover pocked with wormholes, scoring and other damage. The leather cover’s scalloped decorative edge is still visible, and on its front a flower – perhaps a narcissus – a little less than 2.5 cm in height is tooled into its centre. The half-cloth binding, newer than the leather, has a waxed texture to it.

A new pastedown and end page have been inserted before an end page from a prior rebinding. That previous end page, in pale blue, contains writing in at least 3 different hands. At its top, a pencilled handwritten English inscription provides the copy’s basic bibliographical data. Beneath this, some words appear in a large brown-inked looping Yiddish or Hebrew script. That script bounds a much more compact handwritten phrase, likely in Cyrillic script, of 4 illegible words. Other faint script in Yiddish or Hebrew, along with a single word in Cyrillic script, appears on this page’s verso.

The same pale blue paper as the above-mentioned end page helped repair some evident damage to the title page recto, which lacks most of the previously described main decorative frame. A black ink stamp with the words “Printed in the USSR” – an obviously false statement regarding this edition -obscures some of the publishing information located in the lower, centrally-located illustration of a wreath. On the bottom of the verso, a handwritten black-inked Hebrew inscription runs vertically in the blank space along the spine. Subsequent repair work on the page makes it difficult to decipher this writing.

Minimal, black-inked handwritten marginalia appears, rarely, in a handful of places throughout this copy. About halfway through the entire volume, a section of 14 leaves shows evidence of moderate pest damage.

This copy’s final page bears what appears to be either a stamp or hand-lettered rectangle in Cyrillic script. The blue end page from the earlier rebinding is absent here, with only the later rebinding’s end page present. It, along with the pastedown, is blank except for the ex libris plate of Hyman R. Ressler that provides us with proof that the Library acquired this copy from him and not via the post-Holocaust Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Inc.’s distribution efforts. The bookplate features an illustration of medieval court musicians adapted from the early 14th century Codex Manesse, a book of German songs and poetry; it reflects Ressler’s lifelong patronage of music. Given Ressler’s concurrent reputation as a knowledgeable Jewish book collector, this plate’s location seems curiously misplaced instead of being in its ‘proper’, Hebrew language-oriented location on the inside cover preceding the title page. The back cover has neither the front cover’s scalloped edging nor its tooled flower.

Remarkably, unlike our first copy, this second copy is completely uncensored. Its existence suggests how an anonymous scribe might have been able to reproduce some of our first copy’s missing texts. It also suggests that scribe’s good luck in having access to another copy in the first place – for by the mid-1800s, scholars and antiquarians already considered this edition an extremely rare item.

As of 2020, that rarity has become even more apparent. Online auction sites list only around 10 copies currently for sale, while a small number of institutions – including the Israeli National Library, Hebrew Union College, Yale University and New York’s Chabad Library – hold 15 more among them. The JPL, therefore, is in excellent company.

Perhaps our library could count itself part of an even more exclusive club: our research indicates that all but two of these organizations’ copies are censored to some degree or another. Munich’s Bavarian State Library has the honour of possessing the only complete, completely-uncensored copy of this edition. But for its missing final leaf, the JPL’s second copy of the same edition would be its equal.