Sefer ha-Zohar

(Slavuta [Poland/Ukraine] : Shapiro, 1815, 1827, 1863)

-

The Zohar itself is not one book, but instead a collection of works under a single title. It is usually printed in five volumes, composed of works titled Sefer ha-Zohar al ha-Torah (three volumes), Tikkunei ha-Zohar and Zohar Chadash. The bulk is now attributed to Moses de León, although the Zohar Chadash consists of writings by Safed Kabbalists compiled after the Zohar was first printed. It is essentially a kabbalistic midrash, arranged by weekly Torah portions up to the Book of Numbers, Chapter 29. Beyond that, only three Torah portions appear. The writings include expositions on the portions that are sometimes tangential, exploring subjects only barely related to the portion, as well as legends, homilies, and stories about Shimon bar Yochai. Despite the authorial controversies, the Zohar became and remains the foundational text from which all subsequent Kabbalists built their writings.

-

Although now acknowledged as Moses de León, the identity of the Zohar’s author was hotly contested for quite some time, in part thanks to León himself. Born around 1240 in Spain, he spent his first three decades in Guadalajara and Valladolid before settling in Ávila. Compared to many famous Kabbalists, little is known about Léon’s personal life. He was well-educated and highly-learned: familiar with medieval philosophers, writings on mysticism, and the works of ibn Gabirol, ha-Levi, and Maimonides, for whom his Guide for the Perplexed was copied for Léon in 1264. His first work, Sefer ha-Rimmon (1287) explored ritual law from a mystical perspective; followed by ha-Nefesh ha-Hakhamah (1290) and Shekel ha-Kodesh (1292), both which further explore his kabbalistic thoughts by questioning resurrection and the soul’s transmigration. His Mishkan ha-Edut (1293) discusses heaven, hell, and atonement using the apocryphal Book of Enoch and a kabbalistic interpretation of Ezekiel.

These works were followed, famously, by an Aramaic kabbalistic midrash of the Pentateuch, now known as the Zohar. Upon its first appearance in the late 13th century, it immediately spawned rumours and suspicion. Its original title, the “Midrash de-R. Shimeon ben Yohai”, ascribed authorship to Shimon bar Yochai, a disciple of Rabbi Akiva regarded as a spiritual master by the Jewish sages known as the Tannaim. From the outset, however, many doubted this. After Léon’s death in 1305, these doubts were reportedly confirmed when his widow confessed, to a potential buyer of the manuscript from which León had made his copy, that Léon was the manuscript’s actual author. Apparently, León believed that ascribing the Zohar’s authorship to Shimon bar Yochai would lend it authority and increase his potential profit. Others, however, believe León the true author but wrote it through divine intervention, with the knowledge transmitted through miraculous means.

-

The Shapiro printing family established itself in Slavuta, at that time situated in the Polish province of Volhynia and now in Ukraine. Prince Hieronim Janusz Sanguszko (1743-1812), Volhynia’s final independent ruler, chiefly resided in Slavuta. Sanguszko, like other Polish leadership, considered Jewish residents an integral part of rebuilding cities and developing foreign trade. In 1791, he therefore granted Mosheh Shapiro (1759-1839), Slavuta’s newly-named and unpaid rabbi, permission to open a Jewish press. Moshe was the son of esteemed Hasidic leader Pinchas Shapiro, and a member of the Ba’al Shem Tov’s circle.

Over time, the Shapiros allied their fortunes to that of the Sanguszko dynasty. This led to the Shapiros’ central part in an incredible controversy which demonstrated the Jewish community’s fracturing, and led to unfortunate consequences for them and Jewish printers in general. Yet even up until today, their legacy has lasted — including a remarkable connection to the JPL.

By 1793, the Russian Empire controlled Slavuta and much of formerly independent Poland. Between 1830 and 1831, armed rebellions arose against the Empire. Among the rebels was Hieronim’s grandson Roman Stanislaw (1800-1881), a deserter from the Russian military. When the rebellion failed, Roman was stripped of his civil rights and his land, and sentenced to exile. However, this was commuted to military service in the Caucasus. By 1838, he had regained his nobility and military rank. Seven years later, Roman – now deaf — returned to Slavuta. Heirless, his focus on caring for his estate and its tenants, and ardent financial and psychological supporter of returning exiles, would later be seen by others as a liability, particularly vis-à-vis the Shapiros.Under the Sanguszkos’ aegis, the Shapiro press flourished. Mosheh, an exceptionally talented engraver, designed letters that became known for their clarity and beauty. He printed the first complete Babylonian Talmud, whose paper colour and quality made the press famous across Russia and Western Europe. Eventually, Mosheh’s sons Shmuel-Abba and Pinchas took it over. They manufactured their own paper and typography to ensure the high quality of responsa, halakhic and other works on which their reputation rested. They also employed many local non-Jews as well as Jews. Soon, Shmuel-Abba and Pinchas had transformed the Shapiro press into the Empire’s largest printing house, while cementing their influence in Slavuta itself.

By 1825, Nicholas I ruled the Empire, and he hated Jews. Their quality of life deteriorated exponentially during his reign. Disputes between Hasidim, their traditionalist ‘Misnagdim’ opponents and modern-secular Maskilim – and each faction’s propensity to call out perceived offences – destabilized the entire community internally. Externally, similar reports from converts to Christianity also began reaching Nicholas’s regime.

In the early 1830s, the Misnagdim, supported by the Maskilim, informed the Czar that the Hasidim were printing and distributing problematic, uncensored literature. Their attacks focused on the Shapiros, even though they produced many non-Hasidic works. In turn, the Shapiros tried spotlighting their largest competitor: a Vilna printing house supported by the Misnagdim. Both sides offered inaccurate, incendiary information to the government.

The situation came to a head in 1835. Mosheh, Shmuel-Abba and Pinchas faced accusations of murdering a bookbinder found hanging in Slavuta’s synagogue. Shortly beforehand, they had fired him for drunkenness; but in fact, he had taken his own life. Nevertheless, a priest claimed the bookbinder had intended to deliver an uncensored page from a soon-to-be-printed Shapiro book to the authorities. The text indicated Jews were forbidden to help Christians, even in cases of mortal danger. This trumped-up motive and the circumstances attracted Nicholas I’s interest; he ordered the parties involved face a military court. Those found guilty would face punishment of the utmost severity.

Leading up to the trial, the once-fruitful alliance between Slavuta’s Sanguszko princes and the Shapiros proved fruitless. Prince Eustachy Sanguszko – father to Roman, the former Polish rebel against the Russian Empire – vouched for the Shapiros, whom he greatly esteemed. Nevertheless, the unconvinced court investigator, Count Vasilchikob, formally charged the Shapiros with murder in 1836. He considered their fear of being denounced for printing the book without censor permission as a valid motivation for the crime. Their press was soon closed down.

They were found guilty, partly due to the false testimony of a Jewish doctor who also provided a skewed translation of the unpublished book. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the priest who detailed the bookbinder’s doomed journey had also secured this doctor’s efforts; the Czar subsequently rewarded the latter with funds seized from the Shapiros.

The Shapiros’ punishment was, by far, the harshest ever handed down to Russia’s Jews: 3 years’ prison time in Kiev, followed by enduring 1500 beatings while walking through a gauntlet of guards, the annulment of their civil rights, and ultimately exile (on foot!) to Siberia. Mosheh fell ill in Kiev, dying in 1839 shortly before the beatings. Shmuel-Abba and Pinchas were not expected to survive that ordeal, and their last requests were taken. Younger brother Pinchas, aged 47, asked to go first and to be buried in a Jewish cemetery should he die. During the beating, he prolonged his suffering by refusing to continue walking through the gauntlet until his kippah, which had fallen off, was returned to him.

Both brothers survived, but were so wounded that it took them until the end of 1839 to heal enough to start traveling to Siberia. Bound in chains, they required an entire year to get as far as Moscow. Upon arrival there, they were again detained to allow their health to improve and permit their further travel.

At this point, the Shapiros’ fate becomes uncertain. Some sources maintain they reached Siberia, where Shmuel-Abba died. Others indicate their situation united the fractious Jewish community to save them ; or that a sympathetic prince successfully petitioned the Czar for their transfer to the Moscow almshouse, where bribes to minor officials assured them a kosher diet and allowed visitors, among them Prince Eustachy who forwarded word from their family. In these versions, they ultimately avoid Siberian exile, residing in Moscow for 16 years with no less than 48 medical exams repeatedly confirming their inability to travel onward.

In 1848, a now-repentant Count Vasilchikob appealed to Nicholas I to pardon the Shapiros; the Czar refused. When Vasilchikob became Governor-General of Ukraine in 1855, he repeated his petition – this time, successfully. The Shapiros were released the following year; on their way home to Slavuta, they stayed in Kiev where Vasilchikob housed them and begged their forgiveness. Upon their reaching Slavuta, the entire town celebrated. Each brother became a rabbi: one in Slavuta, the other in a nearby town – which seems to indicate that no matter the proof (or lack of it) of Siberian exile, they survived their sentence. Their printing legacy, meanwhile, also survived it.

For one, Shmuel-Abba and Pinchas’ sons leased the Zhitomir press in 1847, re-establishing the family business. It was the only Jewish press, save Vilna’s famous Rom enterprise, permitted to exist in the Russian Empire between 1836 and 1862. For another, Shmuel-Abba and Pinchas had compiled a scroll during their enforced stay in Moscow, in order to continue their religious practice. During the Soviet regime, it was stolen before being returned to the Shapiro family in the 1920s as part of the Polish-Soviet War settlement. It was eventually donated to Menachem Mendel Schneersohn, the famous Lubavitch rabbi and leader in Brooklyn, where it is still used during the Jewish calendar’s most solemn occasions.

Finally, another descendent of the Shapiro family lives on in the JPL Archives. Chava Shapiro, born in Slavuta in 1879 and best known as a Hebrew writer and journalist, immortalized Shmuel-Abba and Pinchas’s tale in “The Brothers of Slavuta” while living an epic herself. In her late teens and already unhappily married, Chava sought refuge in her writing and spent many late evenings amongst the circle of men discussing their literary efforts in famed Yiddishist and Maskil Isaac Leib Peretz’s home. An affair with Reuben Brainin, the JPL’s founder, prompted her to leave her husband and son and continue pursuing her education. Brainin, however, devastated Chava with his decision to immigrate to North America with his wife. Chava eventually remarried, again unhappily.

Sadly, unlike her ancestors’ story, Chava’s did not end triumphantly, for she was ultimately deported with her husband to Theresienstadt where she died in February 1943. However, the JPL Archives holds more than 200 of her letters to Brainin which, when rediscovered, led to renewed interest and acclaim for Chava as a trailblazer, having insisted upon an education and a life of freedom often granted only to men.

-

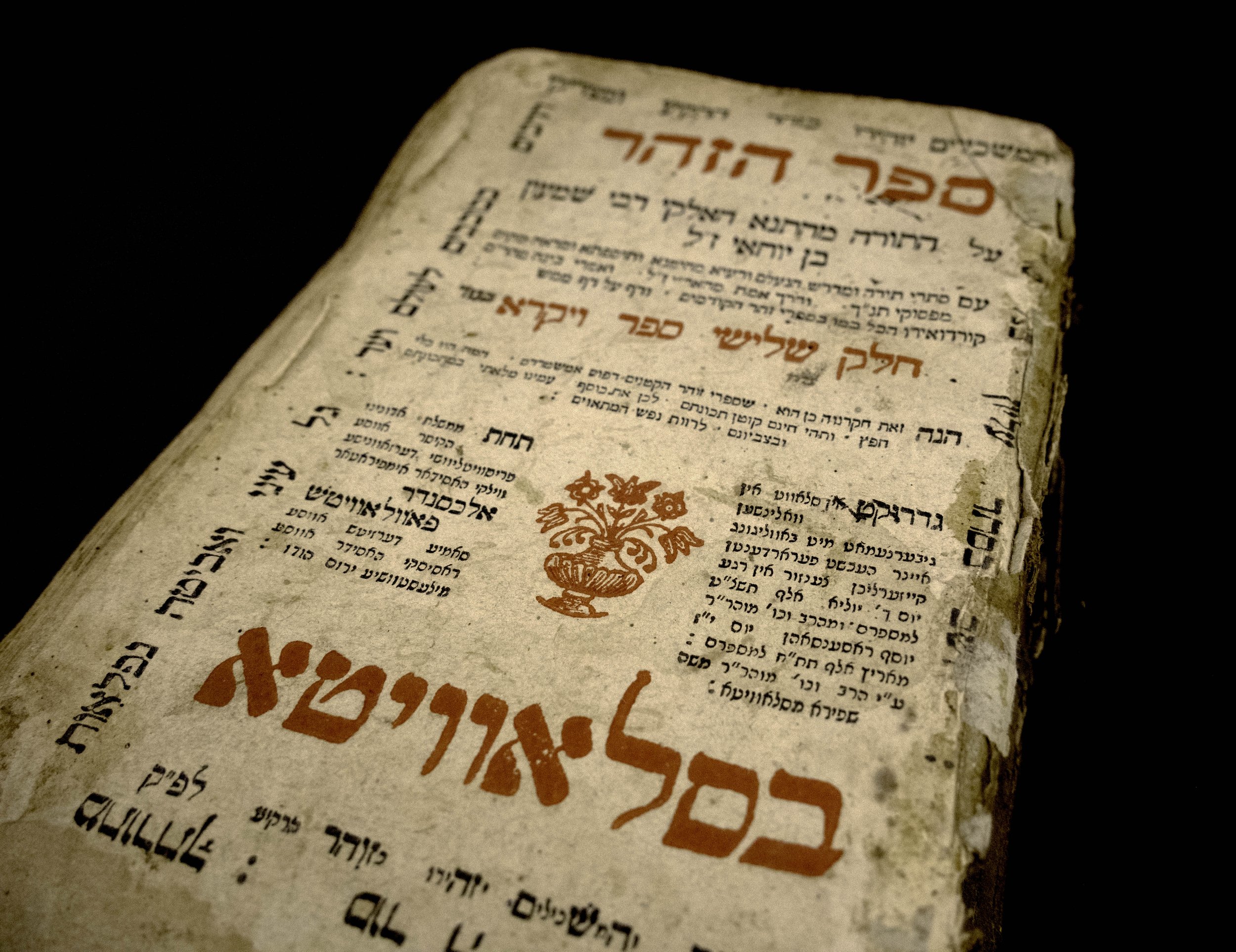

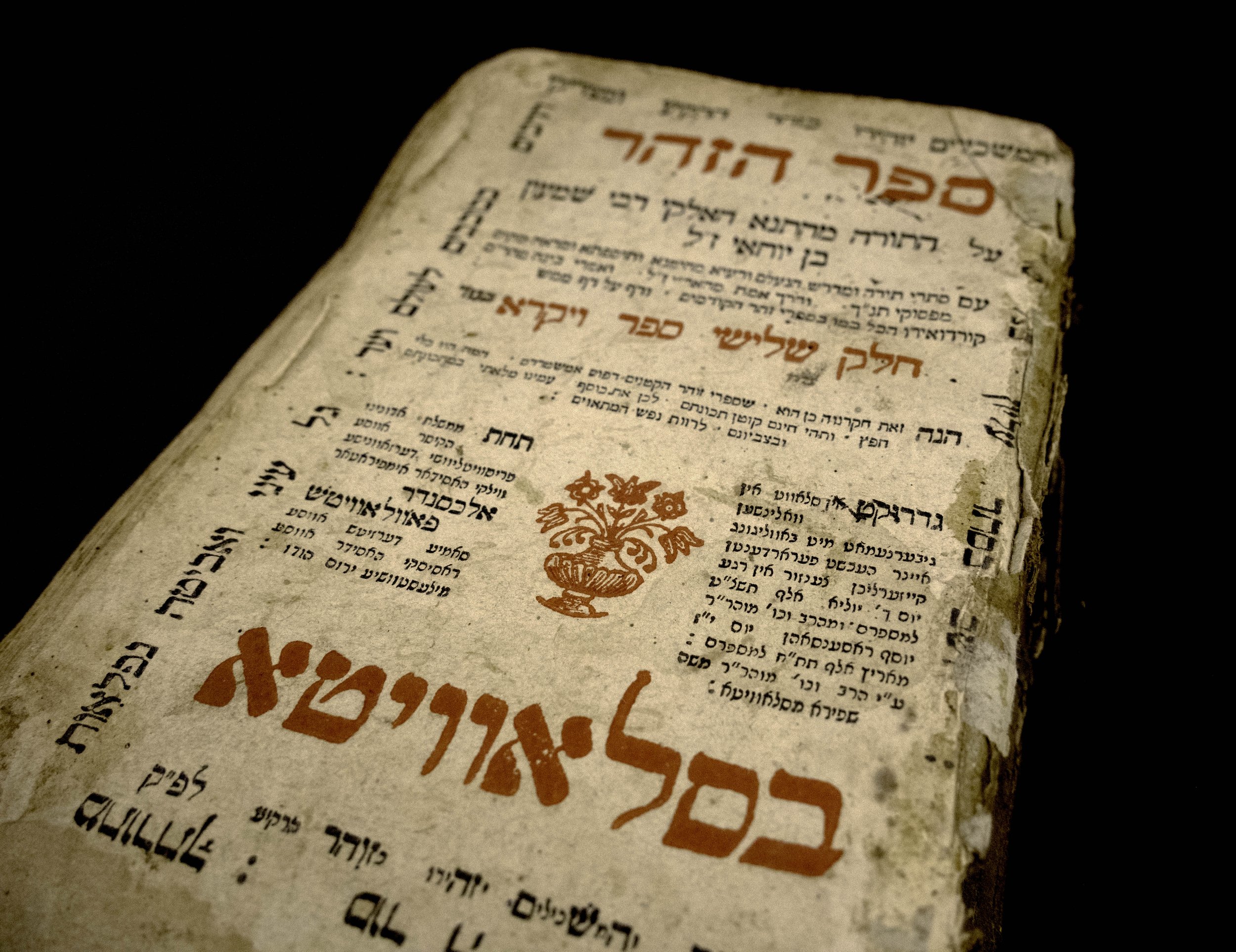

The JPL holds multiple copies of the Zohar printed by the Shapiros: in fact, it holds 3. Two brothers, Moshe and Pinchas Shapiro, printed the first two – one in 1815, another in 1827; and the last copy was printed in 1863 after Moshe and Pinchas’ sons moved their press to Zhitomir.

One 1815 copy measures 20.5 x 13 x 5.5 cm. It was partially rebound, though the original, now-cracked and dirty dark brown leather binding remains visible. A brown cloth wrapping has been added to the still-intact front and back boards, but the cloth is peeling away on the corners of the front and back covers. The spine is covered with a fading, blue plaid flannel, to which a paper strip with Hebrew characters had been adhered at some point. All but the last couple of letters have peeled away.Its title page is highly characteristic of Shapiro printing. The Hebrew title Sefer ha-Zohar is printed across the fold in large, red letters. A central ornament, a vase with flowers, and the place of publication are also printed in red. The text, primarily in Ashkenazi block print, also includes a small section in Rashi script. The front end page, showing minor bug damage, has two signatures in both pencil and purple pen in very large handwriting resembling a child’s penmanship exercise. Likely, other writing appears on the page’s other end, but it has been covered in a 10 x 7 cm piece of paper filled with Yiddish script written in green pen.

Considering the book’s age, its cloth pages are in mostly good condition. Vertical chain-lines run over the pages, and only small amounts of discoloration are focused on the fore edges. There is no marginalia. Small, indistinct and inconsistent watermarks are evident on the leaves. The title page verso contains a short text, perhaps the approbation, in block print. On the following page recto, the text proper begins, with the framed Hebrew word Va-yikra appearing at the top, where someone also wrote in ink in Yiddish, with an apparent 1885 date. Extremely faded script runs vertically along the length of its outside margin. A black-ink stamp, in Cyrillic, appears in the left-hand corner.

The end page appears to have had another page pasted over it. Both show extreme damage and the upper layer has been partially torn away, revealing the layer below. On the upper layer, the ink from the elegantly-written, mixed-language inscription is still fairly clear. However, while its Yiddish text is discernible, the remnant of the Latin-alphabet portion hampers exact identification of the language. The lower layer likely was the original end page; the bulk of the visible Yiddish inscription here appears to be an ink transfer from the upper layer.

The 1827 copy measures 23 x 17.5 x 4.5 cm. It has been rebound, and unlike the 1815 edition, none of the original binding remains. The new covers are red vinyl, with black vinyl along the spine; this is very characteristic of mid-20th century practice. Despite being rebound, the spine is coming away from the new binding along its bottom two-thirds.

Opening the book, one immediately notices the title page has been torn, quite neatly, across the top. The title is missing, yet a minuscule portion of one letter remains as evidence that it too was printed in red. Still, there are minor differences between this title page and that of the 1815 edition: “Slavuta” is again printed in red, but the page ornament has changed, and also now appears in black. It is otherwise similarly laid out, using both Ashkenazi block print and Rashi script, as does the text. A black-ink stamp at the bottom right-hand corner is, unfortunately, smudged and illegible. The title page verso bears a Latin approbation.

Like the 1815 edition, the 1827 edition’s pages are in exceptional condition with very little damage. Unlike the earlier edition, several features make them unique. First, they are in pale blue. As well, they are thicker, with horizontal chain-lines, and rather fascinating watermarks. An ornate watermark is folded into each spine’s gathering, making it hard to distinguish. Numbers are printed, perpendicular to the spine, along the top two chain-lines. On certain pages, there is an “8” on the top chain-line and a “1” on the line beneath it , while on the page following, the corresponding numbers are “6” and “2”.

A floral ornament, not present in the 1815 edition, decorates its final page. An added end page that doesn’t match the original binding — and is superfluous to the new binding’s end page — separates the work from the new binding. This indicates that this copy was perhaps rebound previously, which would render the pages’ state within even more impressive as it suggests significant handling despite a lack of marginalia or other indications of use.

Our 3rd copy, printed in 1863, measures 24 x 17 x 4 cm. It was rebound in marbled boards; fabric covers its spine and corners. On opening the volume, one manila leaf serves as an endpaper, followed by another, loose manila leaf.

The verso of the book’s 3rd leaf – greyish paper that has been pasted in – contains black penned-in Yiddish cursive inscriptions and a small, illegible black-ink stamp with a design. Its recto bears penned, red-inked cursive inscriptions, likely Cyrillic, and two smaller, pencilled-in columns of numbers.

The copy’s title page, printed in red and black ink, displays the same ink stamp as on leaf three; however, here it is quite legible: the letters “S.L.” are shown in an Old English or German Fraktur typeface.

The recto of the copy’s final leaf of text proper shows the same ink stamp, if slightly less legible than on leaf 3.2 manila leaves, similar to those at the book’s opening, appear at the back of the work.

Two aspects of all the Shapiro Zohars held by the JPL typify their reputation for high-quality printing. Their margins are evenly spaced. As well, they feature a unique stylistic choice of fonts: while using Ashkenazi block print for headings, page numbers, and the text at the top of the page, the bulk of the text and the marginalia are all printed in Rashi script. All these Zohars consistently follow this format, which differs from the Shapiros’ non-Kabbalistic works held by the Library. Notably, a contemporary 1815 Zohar printed in Shklow (Belarus), also held by the JPL, mimics the Shapiros’ choices of fonts.