a gift

for the

children

exploring the beautiful illustrations in Yiddish children’s literature : Part I

In-House Exhibition March 13, 2023 - June 11, 2023“Yiddish children’s literature, deeply preoccupied as it was with themes of identity, narrow escapes, fortuitous twists of fate, and the exercise of power, seems more relevant now than ever.””

A grandmother who fights off bears; mischievous monkeys, outwitted by a horse; a little girl and her magic parasol; the story of a stray dog, which I’m sorry to report doesn’t have a happy ending.

The Yiddish children’s literature found in the JPL collection includes a wide range of stories in content and style, attesting to the richness of Jewish storytelling and literature. Like children’s literature from many cultural backgrounds, illustration and font design play an important part of the volumes featured in this exhibition. For many artists and writers, this budding field of children’s literature presented a playground for their craft, a space where they could experiment with style outside of the more rigid expectations of publishing geared towards adults. Like being left to play unattended and make your way home by nightfall, there were fewer restrictions and oversight given to the publication of children’s literature in the inter-war years, meaning this genre was a place that many respected authors and artists could experiment with a freedom they weren’t afforded in their better-known work. Featured in the JPL’s ephemeral collections, and in turn this exhibition are artists and writers such as El Lissitzky, Y.L. Peretz and Leyb Kvitko, who made valuable contributions to Yiddish children’s literature and illustration while carrying out the careers for which they are better known. Included in this exhibition are translations of well recognized fairytales, passed across cultures, languages and lands with unknown roots, while others were written contemporaneously to their publishing, in Yiddish.

Some editions featured in this collection come from as far as Moscow, Vilna and Warsaw, and some are much closer to the JPL, such as New York City and our very own Van Horne Avenue in Montréal. This featured exhibition is divided into two parts: Part I highlights Yiddish children’s literature from the interwar years, and Part II, coming to JPL-Curates later this year, will be dedicated to post-war Yiddish children’s literature.

Dos goldene ringele

The golden ring, c. 1917-1920

It is clear that this one was well loved by children for many years, as it is missing its cover and young hands seem to have tried to colour in the illustrations on one page.

This rhyming story “told to my child, Moishele” is about a child who loses a golden ring and goes on a quest to ask all of the animals if they’ve seen it. The illustrations seem to have an Asian influence, with quick strokes reminiscent of Sumi-e, Japanese ink wash paintings. Many of the animals are depicted as being bigger than the child, adding another magical component to the quest they undertake.

dating this book:

We’ve dated this book between 1917 and 1920 for two reasons: the union that published it, and its orthographic choices. It bears the Jewish Democratic Teachers Union logo on its title page, which appears to have been most active in 1917 and tapered off into the 1920s. Moreover, the USSR standardized Yiddish orthography in 1920 and this book uses Hebrew spelling standards for Hebrew-origin words, indicating that it was most likely published in this small window of time.

It was printed in Kharkiv, Ukraine (one of the centres of Yiddish culture in post-revolutionary Ukraine, along with Kyiv.) While its title indicates the author as Mark Hochberg and illustrator as simply Steinberg, we were unable to find any information about either of them in our research.

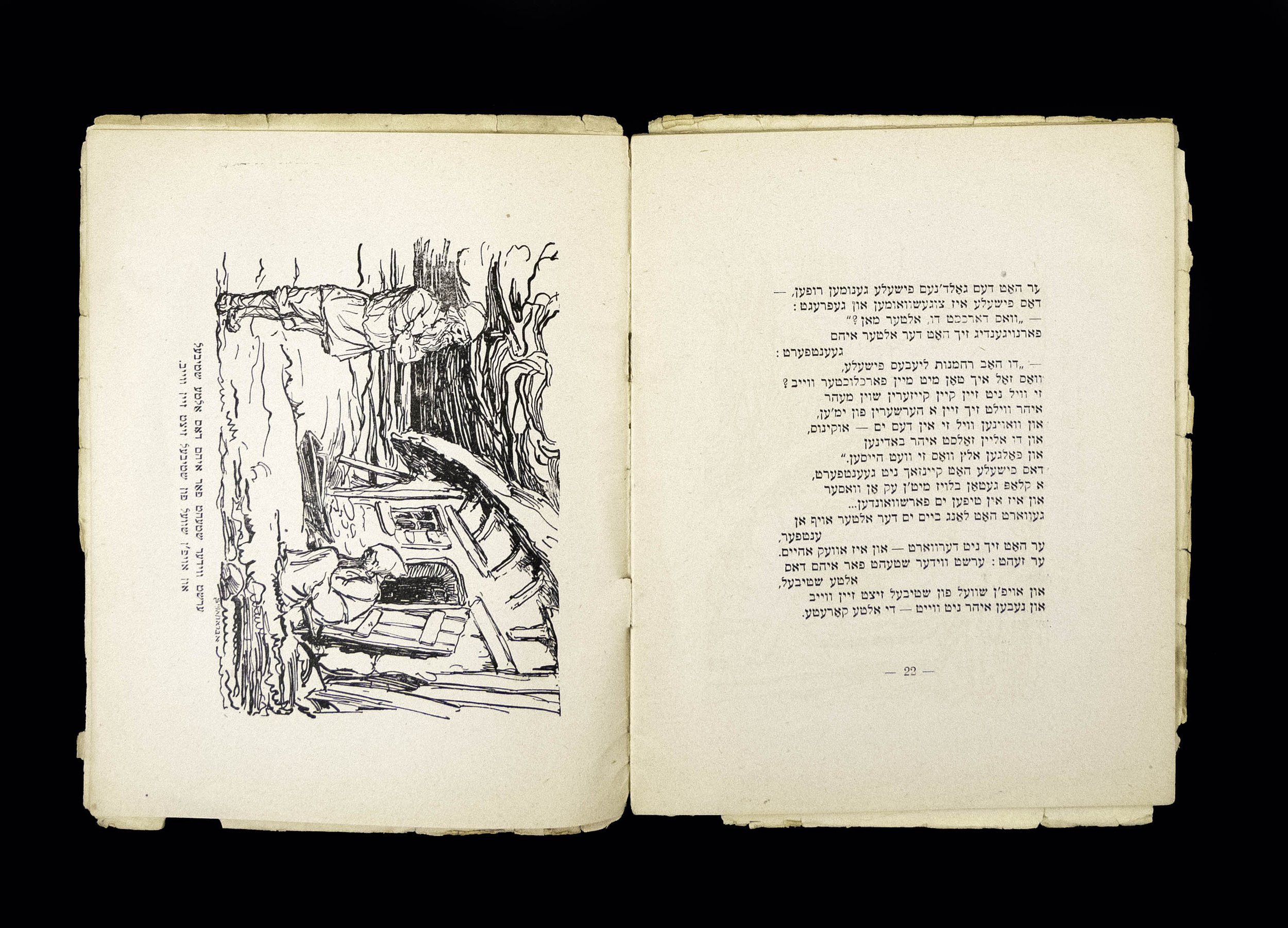

A mayse vegn a fisher un a fishele

a story about a fisherman and a fish, 1919

Written by Russian Romantic Poet Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837), the true provenance of this folktale is unknown, but is often traced back to the Brothers Grimm. While the Russian version is more rigid in poetic structure than Nokhum Yud’s translation in this copy, the Yiddish version maintains a spoken rhythm that adds a layer of entertainment for more advanced readers, making it a great read for children and adults alike. It features full page illustrations every few pages, with key quotes from the text captioning each image. The illustrations by A. Abramovich, which are most likely lithographic prints, are done in a style typical of Romantic artists’ landscape sketches, not unlike those of JMW Turner or John Constable. The use of this illustration style helps match the sense of chaos and risk present in the story, as well as the extreme movements of sea and sky typical of the story’s setting. One of the pages you see here is the part in the story where the golden fish grants the fisherman and his wife their wish of a new house, yet his wife is still unhappy.

This item was created as a monthly serial called Far aykh un ayere kinder (For You and Your Children), where an annual subscription would get you twelve such volumes by post. It was produced by the Jewish Book Agency (at 201 East Broadway, New York) and like Dos goldene ringele, uses Hebrew spelling for Hebrew-origin words, which continued to be mainstream in North America compared to European counterparts at the time of its publication.

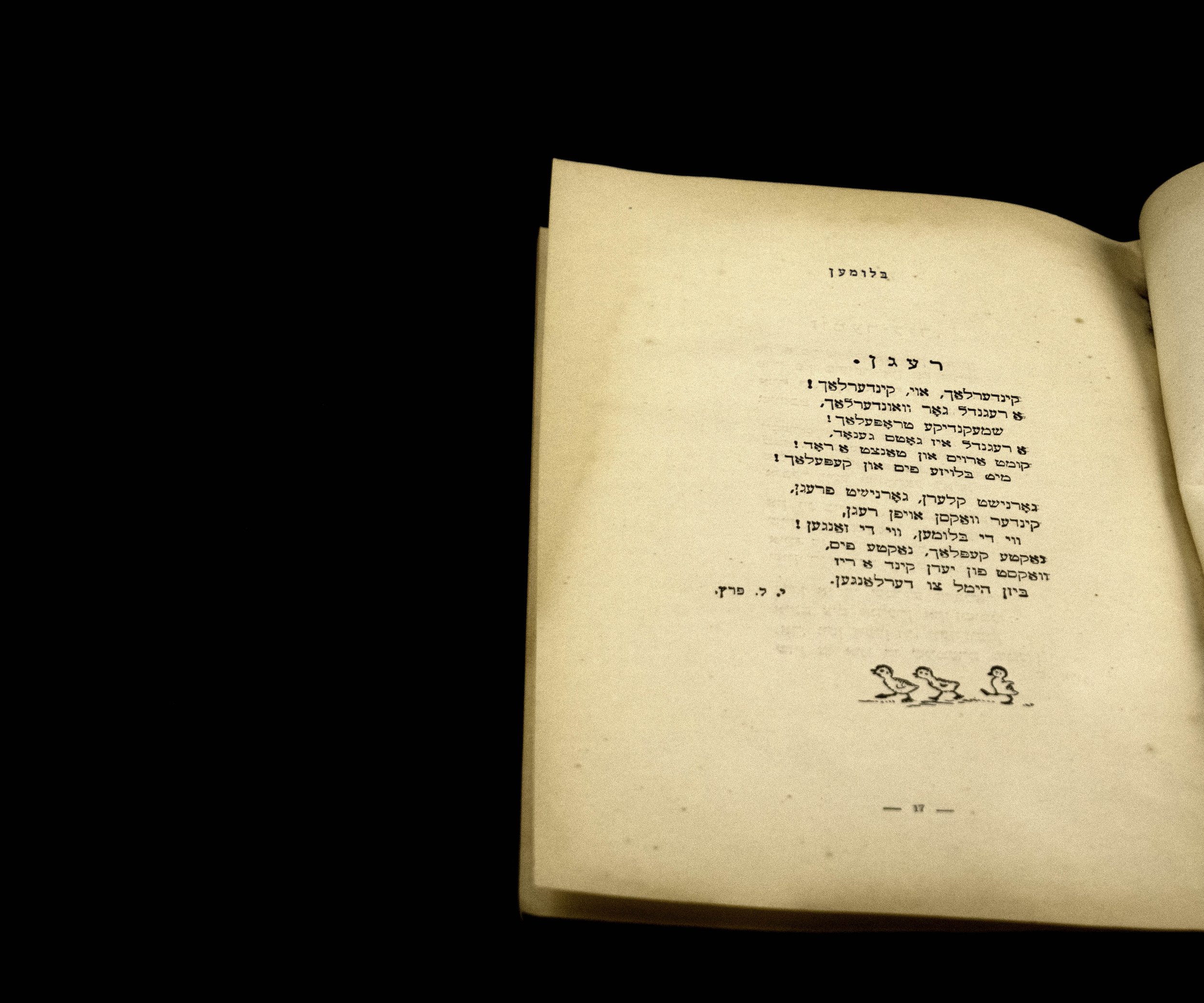

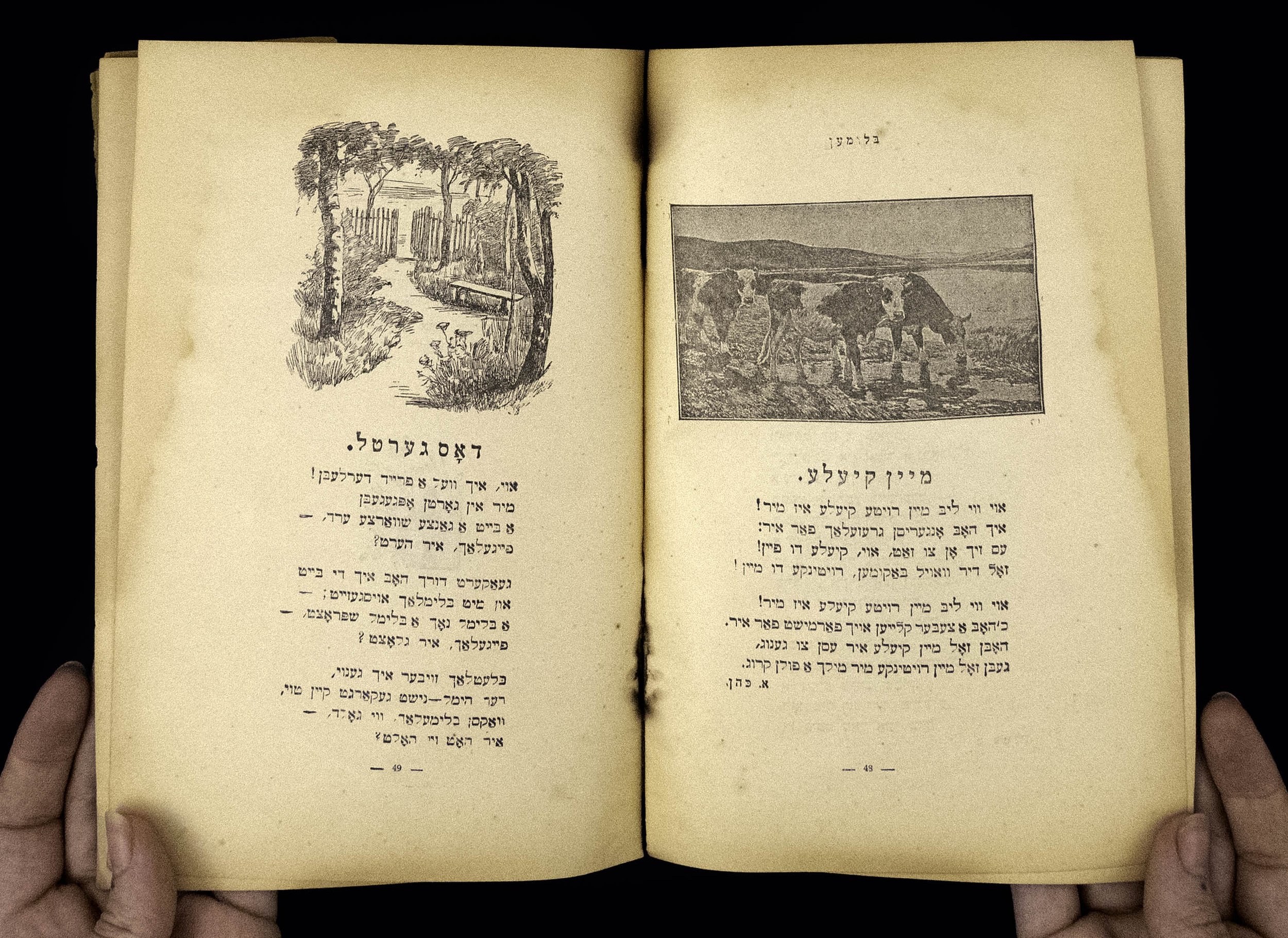

“Blumen” poezye far kinder

Flowers: poetry for children, 1919

Also missing its cover and with rusted staples keeping its contents united, this little volume is a collection of short poems about flowers and nature, written by a range of authors and including an equally wide range of illustration styles in the accompanying prints. The illustrations in this book are eclectic; some are prints made from drawings, while others look like photographic reproductions. This wide range of styles (and lack of acknowledgement of any illustrators names) likely indicates that the illustrations were submitted alongside each poem.

Blumen includes a poem by Y.L. Peretz (1852-1915), one of the most famous Yiddish authors of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Peretz’s poem is about little kids dancing and growing in the rain like flowers.

Published in 1921 in Vilna, Poland (present-day Vilnius, Lithuania), this book was a re-collection of poems from 1914-1915 that had run in the first Yiddish children’s magazine called Little Green Trees also out of Vilna. The title ‘Little Green Trees’ itself comes from a 1901 poem-turned folk song by Haim Nachman Bialik (1873-1934) about children so gentle they could blow away in the wind.

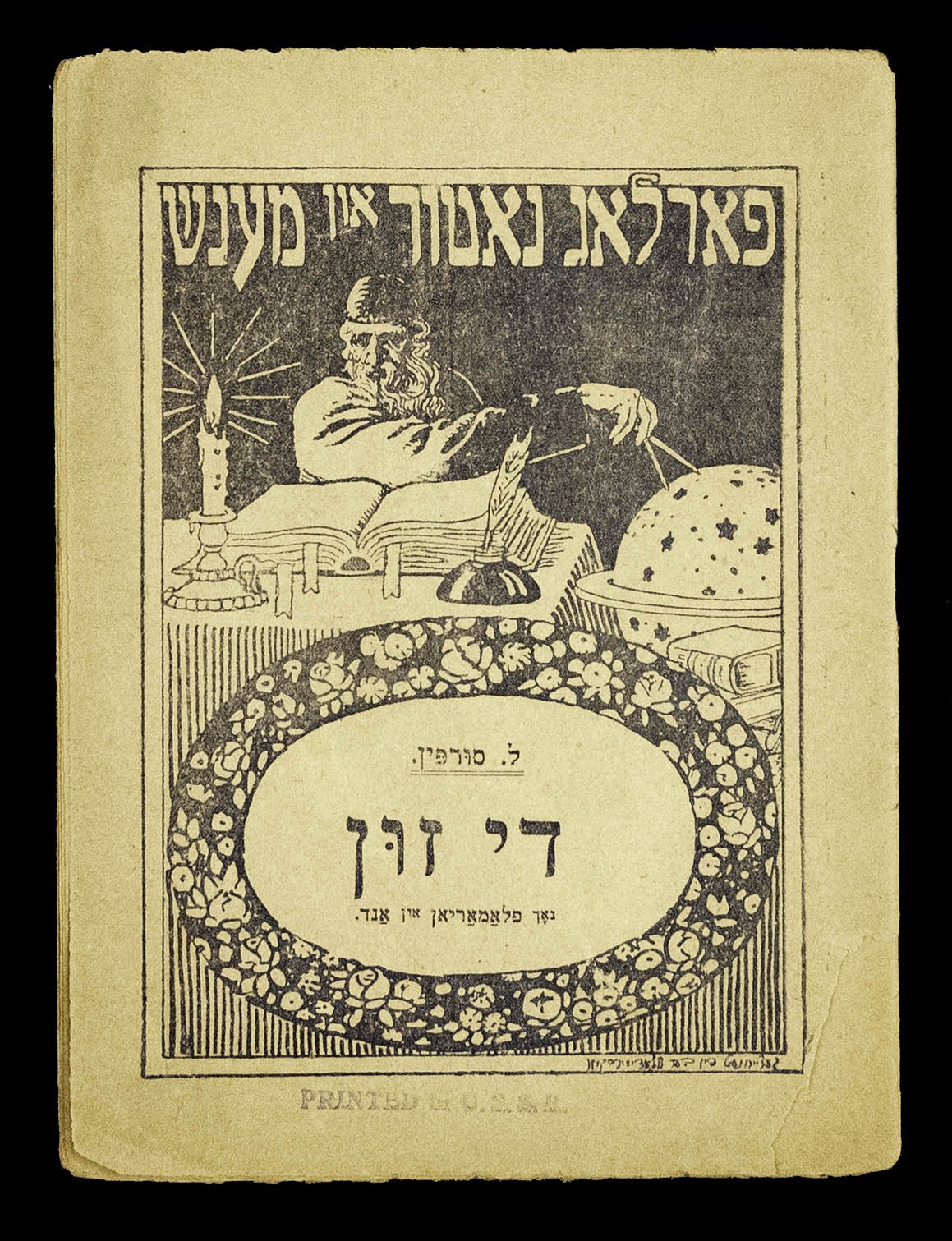

Di zun

The sun, c. 1922-1926

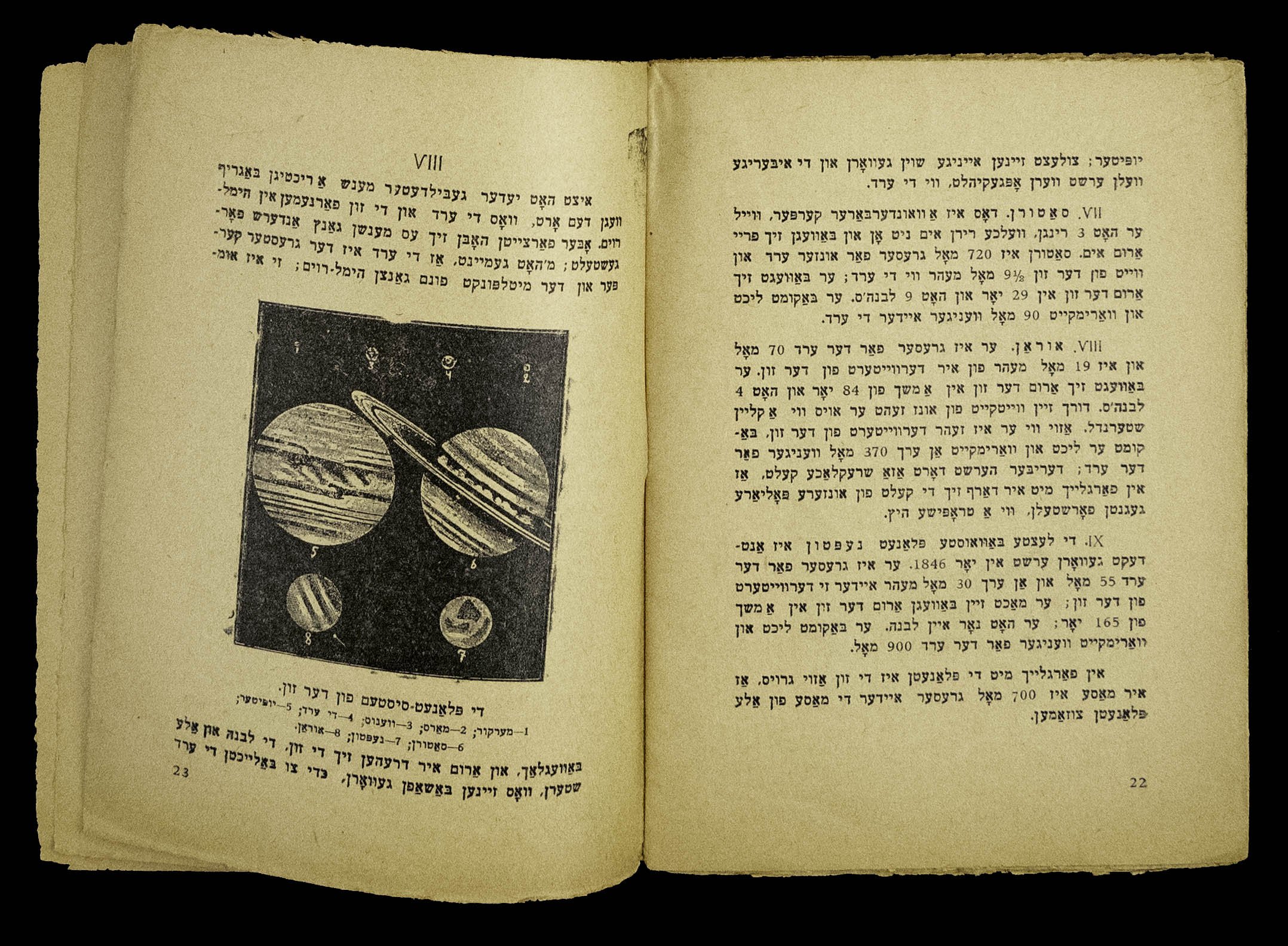

“If you were to ask someone what is the most important light, and they were to say it is the sun, that person would be right!” Upon first glance this serial seems like a story about a wizard; on second glance it seems like a planetary textbook, which is closer, but consulting its contents makes it clear that it is far more poetic than we are used to for science books today. It also manages to combine Soviet propaganda with recognized physics, like when it focuses on movement as life and rest as death. Formatted like many of the other books in this series, this one was actually geared more to adults who wished to pursue education on their own. The cover illustration is a representation of a Renaissance astronomer, with all the same tools of the trade as Dutch Golden Age painter Gerrit Dou’s De astroloog (1650-1655): large books and a globe, lit by candlelight. The entire issue is printed in black and white, illustrated using either woodcuttings or etchings, based on the thin notchings to fill the darker areas. The illustrations within are sparse, and less narrative than their cover, but still balancing aesthetic concerns with scientific representation - especially evident with prints like the solar flare on page thirteen.

The textual content does not shy away from the morbid metaphysical musings often brought on by pondering our place in the solar system. It talks about what will happen when the sun dies, referring to the universe through a metaphor of a cemetery on numerous occasions.

“Everything that has a beginning also has an end – there will one day be a day that the sun sends out its last rays [...] Be calm and don’t think about the end of the world.”dating this book:

The book is undated but given its subject matter, the mentions of specific scientific phenomena act as helpful indicators, as does its orthography and place of publication: mentions of Neptune as the last planet (until Pluto’s discovery in 1930), as well as discussions about the most recent solar eclipse visible in Russia in 1914 and the next upcoming one in 1927. Given that it uses pre-soviet orthography liked Dos goldene ringele and A mayse vegn a fisher un a fishele, it must have been written in the nascent years of the USSR before standardised Yiddish was as strictly enforced. Lastly, the title page indicates that it was printed in Ekaterinoslav, which was the name of what is now Dnipro in Ukraine until 1926. So, given all this, we assume that Di zun was published in the window from 1922-1926.

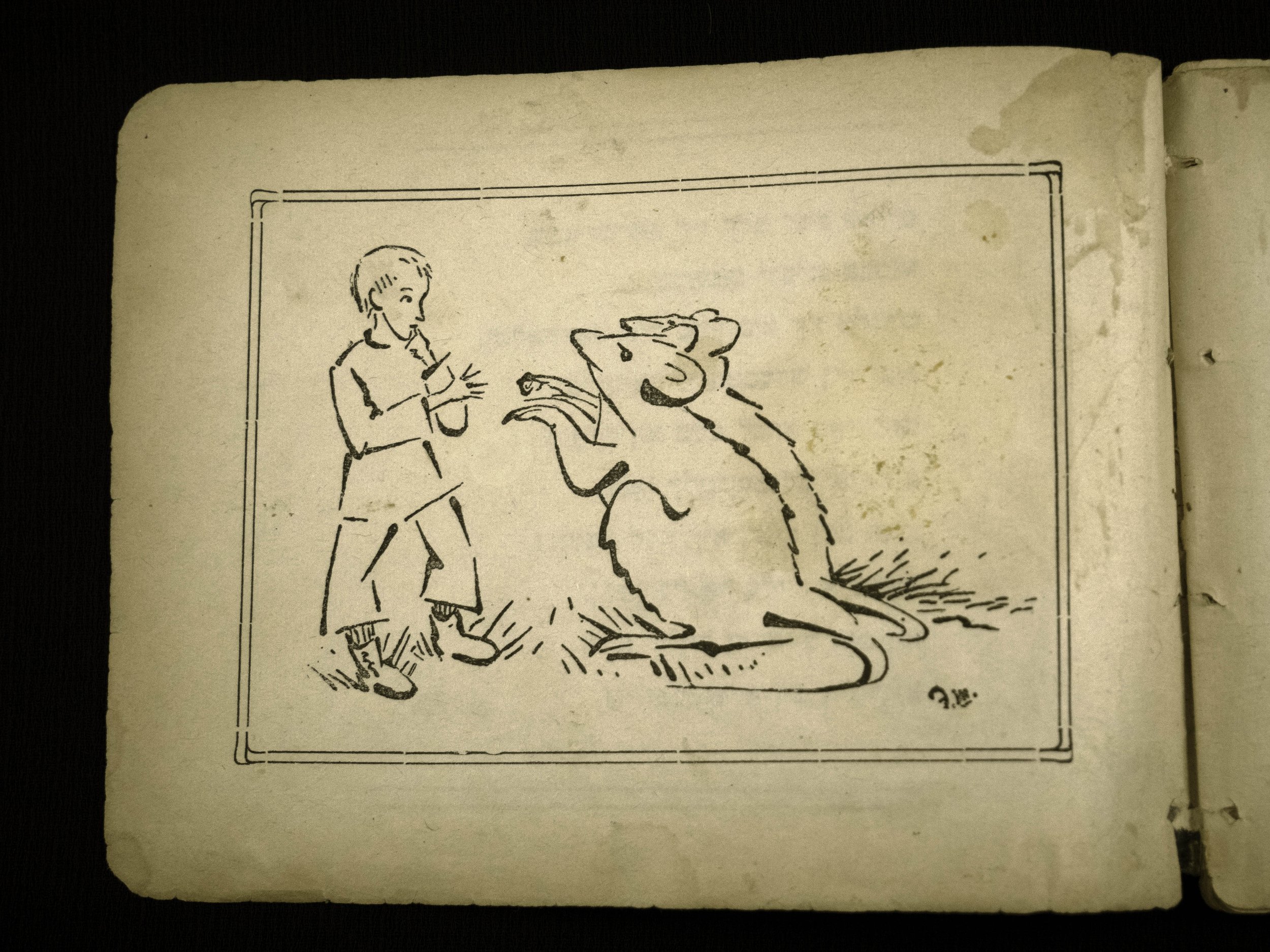

Dos ferd un di malpes

The horse and the monkeys, 1923

Originally written in German by the cartoonist Wilhelm Busch, this ‘Yiddishized’ translation from 1923 by the prolific writer Yoysef Tunkl under the pen name Der Tunkeler (‘The Dark One’) is a short story in rhyming couplets. Der Tunkeler impressively managed to retain the rhyming scheme in his translation. For her Yiddish literature anthology Honey on the Page, Miriam Udel purposely excluded translated works, except this one, thanks to Der Tunkeler’s ability to shape the flow and rhyming verses in his Yiddish version so artfully as to make it a “second original”.

This short book of fourteen pages includes black line drawings on each page illustrating the scenes of the surrounding text. While Der Tunkeler was known to Yiddishize or Judaize the corresponding illustrations to Busch’s texts as well - changing characters’ facial features and garb - it does not appear to have been the case for this story, which doesn’t include any human characters. The style, however, doesn’t match the way Busch often drew either animal, which feature frequently in his stories, so it can be assumed that while Der Tunkeler didn’t adjust Busch’s depictions, he did re-illustrate the scenes for his translation.

From German, to Yiddish, this poem has been translated to English by Miriam Udel as well, maintaining its rhyming pattern. While you can find the Yiddish version in the copy seen here in the JPL Special Collections, you can read the English translation among many other Yiddish children’s tales in Miriam Udel’s Honey on the Page.

bertshik, 1927

Leib Kvitko’s long-form rhyming poem Bertshik tells the unfortunate story of a dog whose caretakers misinterpret his repeated attempts to help, leading to his end. Tragically, Kvitko’s life ended equally during the night of the Murdered Poets, along with twelve other members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee.

It is currently unknown whether there was music composed to accompany this poem, as was often the case for many Kvitko’s works. The inside cover indicates that this poem was dedicated to a Yiddish school in Moscow, notable in that until 1917 Jews were hardly allowed to live in Moscow, so this school must have been quite new. Either woodcuts, linocuts or lithographs, the beautiful black and white illustrations by an unnamed artist accompanying this poem move up and down each page in an airy, dynamic chaos befitting the uncertainty of the dog Bertshik’s fate until the final page. In the third image featured above, you see Bertshik bite the ice delivery man after he has been chased from his home for trying to warn against robbers. R.I.P. to sweet Bertshik, who was only trying to help.

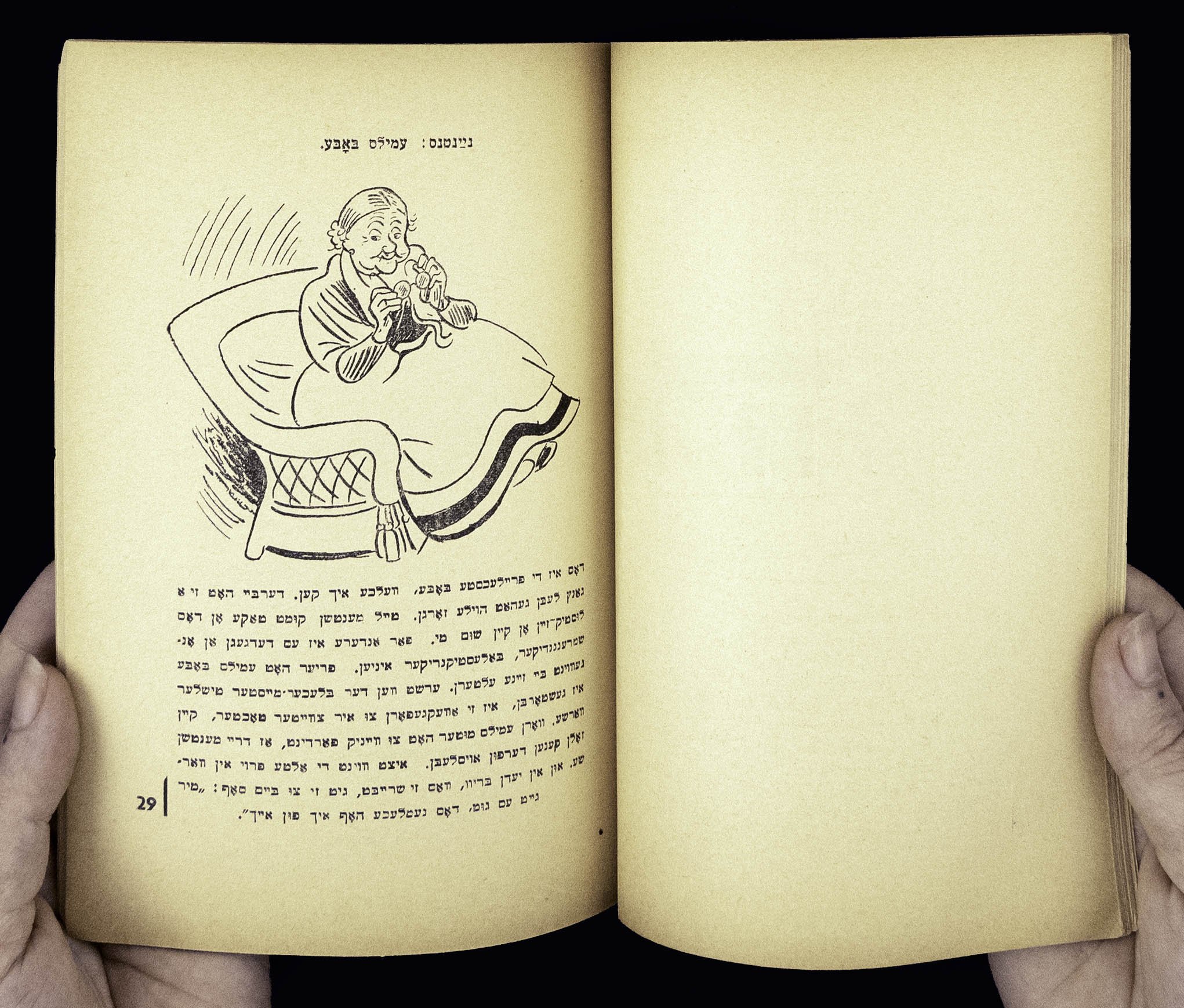

emil un di detektiv

emil & the detectives, 1935

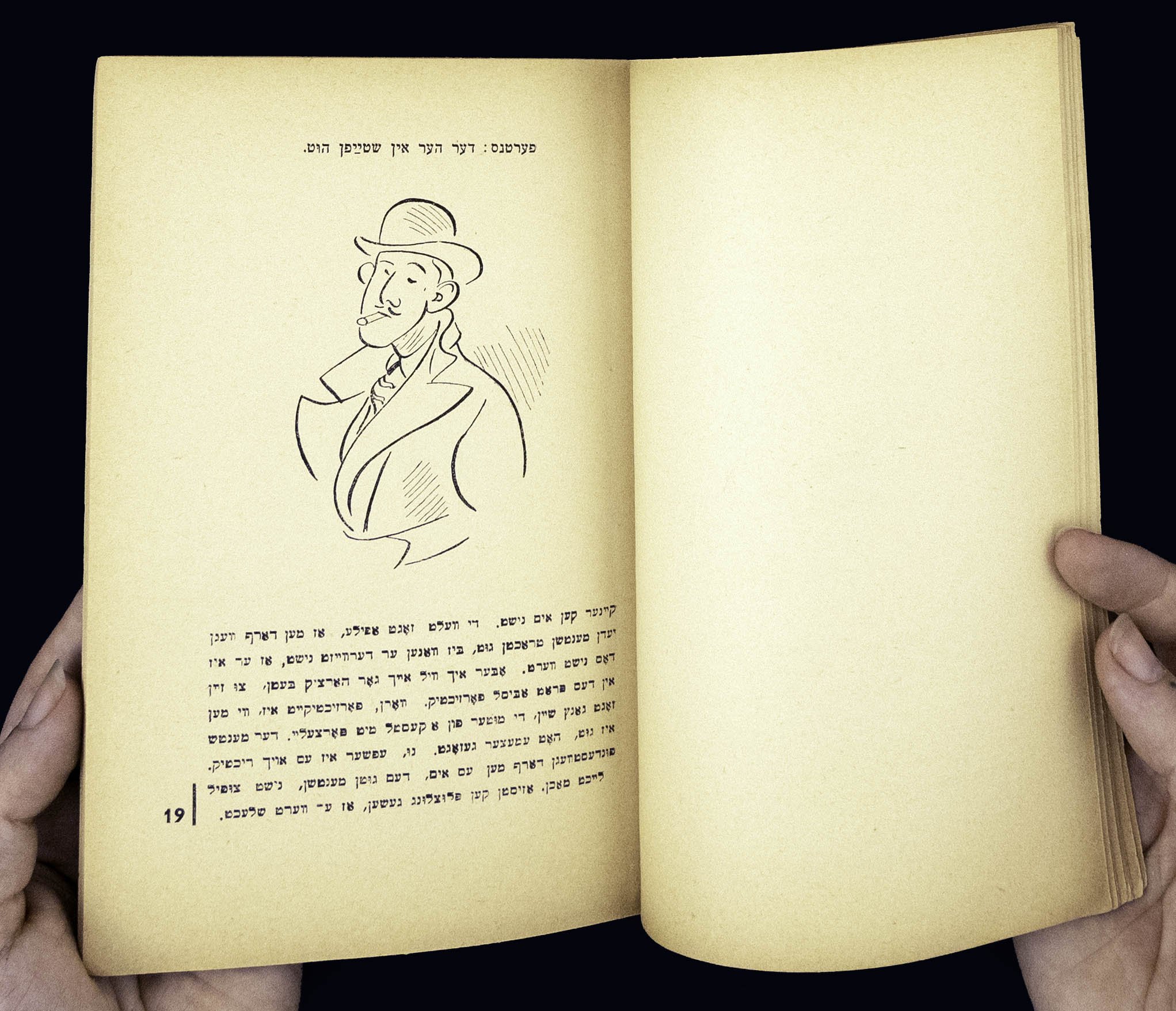

This story might be the most widely known of all the ones featured in this exhibition. Written in 1929 in German by Erich Kästner, it has been translated into 59 languages, is still in print, and has been made into several movies over the last 90 years. The copy we have in our collection is actually part one of the serialised Yiddish version produced by Kinderfraynd, and thus only includes the first three chapters of the story. The back of the book makes a big deal that it now has illustrations, suggesting that this may be one of the first editions in which Walter Trier’s drawings are included.

A few elements of this volume stand out. After the introduction, more than half the book is devoted to providing full page profiles of each character in the story–their likes and dislikes–without revealing their part in the plot. Most are people but some are more abstract; like on page seventeen when we meet “a rather important train compartment.” Each has a portrait accompanying their description, some placed into their context. Kästner’s story begins after the profiles, with sparse illustrations in each short chapter. The assumption for the profile inclusion is to help give context to early level Yiddish readers, making the story more accessible for a wider range of comprehension levels. It could also be playing on the genre, where detectives keep brief profiles of the important players in their investigations.

This original German story from 1929 stood out amongst other children’s books of its era in that it was set in the contemporary city of Berlin, not an ahistorical anywhere town or fairytale land. A film adaptation followed quickly in 1931, yet by the time this Yiddish serialised version was printed in 1935, the Nazi regime had already been in power for two years; Berlin was no longer the safest setting for a young boy to be wandering alone, especially when the translation catered to a Jewish audience. In addition to the usual translation of names, the Yiddish version adjusted the setting of the story to Warsaw, making it even more relevant to its young audience.

PLEASE VISIT US AT THE JEWISH PUBLIC LIBRARY FOR THE COMPANION EXHIBITION FEATURED UNTIL June 11, 2023.

Meet our collaborator

This exhibition was a joint effort featuring the work of our Education Outreach Coordinator, Ellen Belshaw, as well as one of our resident scholars, Shlomo Jack Enkin Lewis.

Shlomo is a Jewish Studies student working towards an honours B.A. at McGill University. Their work as a language specialist for the Yiddish Book Center's Wexler Oral History Project and experience as a translator have prepared them well for engaging with the JPL's archives and special collections. As a native Yiddish speaker, they are passionate about preserving, studying, and promoting access to Jewish history. They see the potential of historical knowledge and preservation to inspire and enliven the future.